Coaching the high-performing key account manager

26th June 2019 | Mark Davies and Richard Vincent

Highly skilled, highly capable key account managers are essential for any organisation seeking to transform to a KAM culture.

As more organisations realize that having a strong KAM capability is an absolute necessity to manage the customer base where most of their business resides, increasing focus is being placed on finding those key “few things” that guarantee success. Through research and working with blue-chip organisations, Cranfield has found that KAM needs to be treated as a fundamentally different business approach rather than an add-on to the existing model or just an extended training programme for salespeople.

This KAM business model has three constituent parts. Firstly, a KAM strategy that looks at what the organisation wants to achieve and how it will get the required capabilities. Secondly, a broad set of organisational KAM standards, looking at: people, structure, planning, data, processes, and culture and leadership aspects. Thirdly, a long-term transformation challenge that come with the recognition that KAM is a very different business model linking very strongly with the culture and leadership standard.

KAM programs are complex. They require organisation-wide approaches and investment, and there is no escaping the fact that one critical component of any high-performing KAM approach (confirmed by all of those who have been successful at KAM programmes regardless of industry or market) is: “You will need highly skilled, and highly capable key account managers.”

Dr Chris Shambrook: Feedforward, not feedback.

This might sound obvious, but it is often overlooked. One reason for its criticality is that organisations seldom get all of the standards and new ways of working right immediately. Data systems struggle to provide the right information, structures are built around products rather than customers, and new planning systems often take time to become accepted as part of the new culture. While these things are maturing, and then as they evolve, it falls to the key account managers to make things happen and build the high-impact value propositions for the increasingly complex and demanding customers.

Reluctant to change

With this in mind, the April 2019 Cranfield KAM Best Practice Forum dedicated a day to looking at how to coach and improve the performance of key account managers and their teams. To help with this, Dr Alison Sanders, Clinical Director of Urgent Care and Emergency Services, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust in London and Dr Chris Shambrook, Director PlanetK2 (a consultancy that takes lessons from elite sports and applies to the business world) were invited to share their experience and learnings. We wanted to learn how to get key account managers performing with high impact in organisations that may be slow to accept change and new ways of working.

Dr Alison Sanders: Measure success on being your best, not the best.

Communication at incidents

The first session of the day was given by Dr Alison Sanders who came to share her experience of getting the best performance out of individuals and teams under extremely difficult circumstances. Alongside her leadership role, Dr Sanders is an A&E Consultant and a doctor on London’s Helicopter Emergency Medical Service, HEMS (aka the air ambulance). She has also been an Olympic rower, a member of the UK Women’s 8 at the 2000 Olympics in Sydney and team doctor for the UK Olympic rowing team at Beijing.

Dr Sanders concentrated on the importance of understanding and controlling the factors that impact the ability of individuals and teams to work most effectively. For HEMS, being able to form teams quickly from scratch is imperative. Often the people on site at an incident may only have just met.

Historically, HEMS members had a reputation of being bossy and abrasive, but it was soon realised that this needed to be changed to improve performance and a lot of work has since been done on improving communication style and effectiveness. Quickly working out who people are, remembering their names and identifying the key individuals in charge of other teams (such as police or fire-service) is vital. Understanding how your own communication style comes across, reading individuals’ responses and then being able to adapt your style accordingly is also key.

Understanding how your own communication style comes across, reading individuals’ responses, and then being able to adapt your style accordingly is also key.

Other things that help to ensure that the team can work at maximum effectiveness are making sure that, wherever possible, there is 360-degree access to the patients, so that as many team members can contribute, and that the layout and environment is as standardised as the site and situation allows, allowing everybody to work in the manner that has been rehearsed.

The inevitable complexity and pressure of HEMS incidents and the sheer number of things that individuals need to process can easily overwhelm people’s available thinking bandwidth. This can lead to situations where individuals are simply not able to process any new information. This usually becomes apparent when people appear to be no longer able to hear or understand even quite simple communications or instructions.

Training

However, it is important to realise that this bandwidth effect impacts everybody to a certain degree, even when the symptoms are less obvious. Therefore, reducing the number of things that need to be decided or thought about, can make a massive improvement to everybody’s capabilities to perform at their best. Within HEMS, a huge amount of effort is put into training, implementing routines and preparing equipment so that all the minutiae of each incident do not need to be thought about by the participants.

- Take complete responsibility for preparation & equipment.

- Do the training – ensure you have the skills and knowledge.

- Rehearse physically and mentally.

- Know yourself. Know how you are under pressure.

- Know how to maximise your own bandwidth.

- Be aware of your own triggers for emotionally difficult scenarios.

- Debrief everything honestly. Why did it go well?

- Be authentic, ask for help when you need it.

- “Park the baggage.” Compartmentalise and leave outside worries outside.

- Create your own zones both mentally and physically.

- Draw people if you want them.

- Ensure everyone is on the same page.

- “Stay in your own lane” but have someone look out.

- Adrenalin is OK but not too much!

- Focus on the process not the outcome. Don’t let your mind wander.

- Don’t catastrophise. It will go badly.

- Have a positive mindset but with a careful and open mind.

Figure 1: Checklist for working well under pressure.

An example of this is the way that the equipment that is needed by the teams is organised. All the equipment is thoroughly tested and checked by a team member before each deployment, ensuring that everything is working, all batteries are charged, and everything that needs to be is within date. Challenge-and-response check lists similar to those used by flight crew preparing aircraft for take-off are used to ensure the process is rigorous. Once checked, the kit is packed in a pre-arranged fashion into bags that are sealed so that they cannot be modified. This means that every team member knows exactly where each item of equipment will be at the point that it is needed, that they can depend on it working as planned, and they don’t need to expend any bandwidth on thinking about its availability.

Every shift incorporates some training and a lot of effort is put in to thinking of scenarios that would be challenging in different ways. So, no matter what is encountered on site, similar situations will have been rehearsed and planned for, minimising the number of decisions that have to be made from scratch.

Dr Sanders provided a short list of useful tips for working well under pressure (Figure 1). Her final piece of advice was to measure success on being your best, not the best.

Lessons from elite sport

Dr Chris Shambrook led the rest of the session. Dr Shambrook is a director of PlanetK2, an organisation that uses the lessons learned in elite sport to help multiple sectors of the business world think, prepare, and perform like the best. He has been part of the support team for GB rowing since 1997.

Dr Shambrook believes that disciplined preparation is the key to success – most people are aware of this, but still don’t do it.

There is a well-known phrase: “Start with the end in mind.” But Dr Shambrook believes that it is also useful to think about why you do what you do, what was your original motivation for starting, what it is about the job that you love and what you are really good. So, “End with the start in mind” can be really helpful at getting you into a place where you’re free to produce your best performances.

An important role for coaches is to be a constant factor in an inconsistent world helping the athlete or coachee to perform consistently whatever the environment. However, a major difference between coaching for sport and business is that the athletes expect to be on a continuous improvement programme and recognise that as a necessary part of performing at their at peak. In business, performance-improvement programmes are normally seen as a last resort, remedial action, for poor performers, rather than something that everyone should be involved in all the time. In sport, improvement processes are always ongoing, with feedback as frequent as possible; whereas in business, feedback may be as infrequent as once per year.

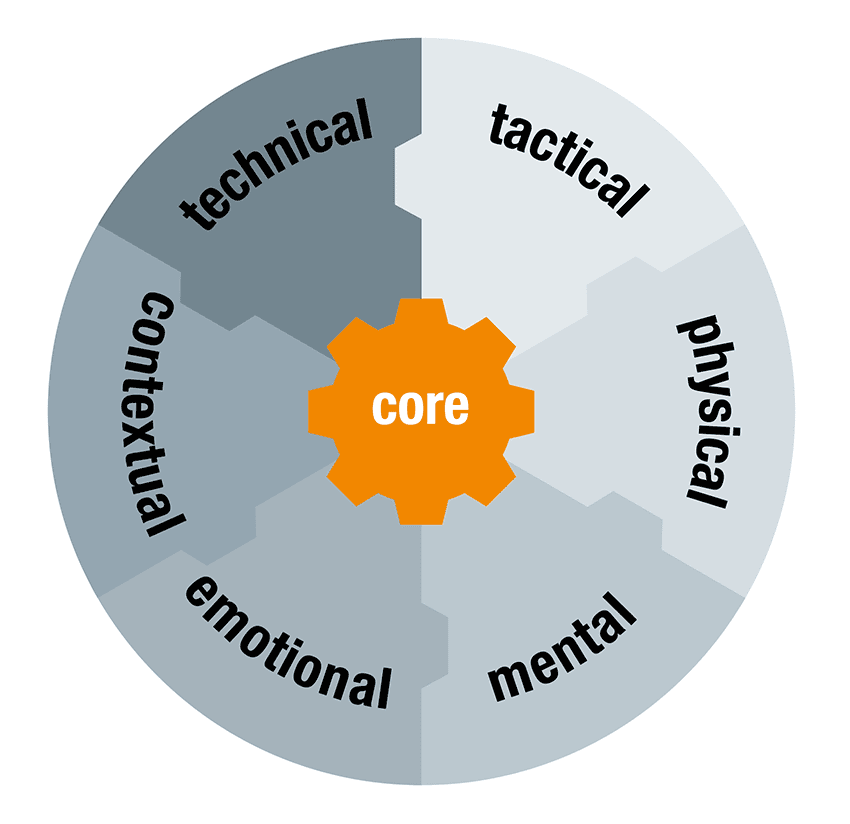

Figure 2: The performance pie.

Roger Federer practices every day even though he knows what to do. The converse usually happens in the business world, even those that should, rarely practice.

A further complication is caused by the interpretation of the term “performance”. Athletes understand that “performance” encompasses all the elements that go towards achieving results and that each element needs to be analysed and honed independently. In the business world, performance is usually used as a synonym for achieving results and is then looked at in isolation from the constituent activities that actually lead to the ability to achieve those results. This disproportionate focus on just the end results, means that learning is compromised and the ability to develop sustainable recipes for winning simply doesn’t happen.

Using the athlete’s definition of performance and changing the focus to the constituent elements (inputs) that contribute to maximizing the chance of achieving the outputs, is the key to making this better.

Dr Shambrook emphasised the importance of coaches having the right mindset and ensuring that within each team there is clarity of responsibility and success. Coaches should be able to answer:

- “What structures have I put in place to that mean improvement over time is inevitable?”

- “How have I helped improvement happen today?”

- “Are we ready for the conditions as they are now?”

It is vital that the development rhythm is daily or even more frequent, and that conditions are constantly being monitored so that any changes can be taken into account. A vital part of all coaching is about making people ready for the conditions they will face and keeping them performance ready.

A good mnemonic for all the elements is to consider them as a performance pie. With motivation as the core at the centre (Figure 2).

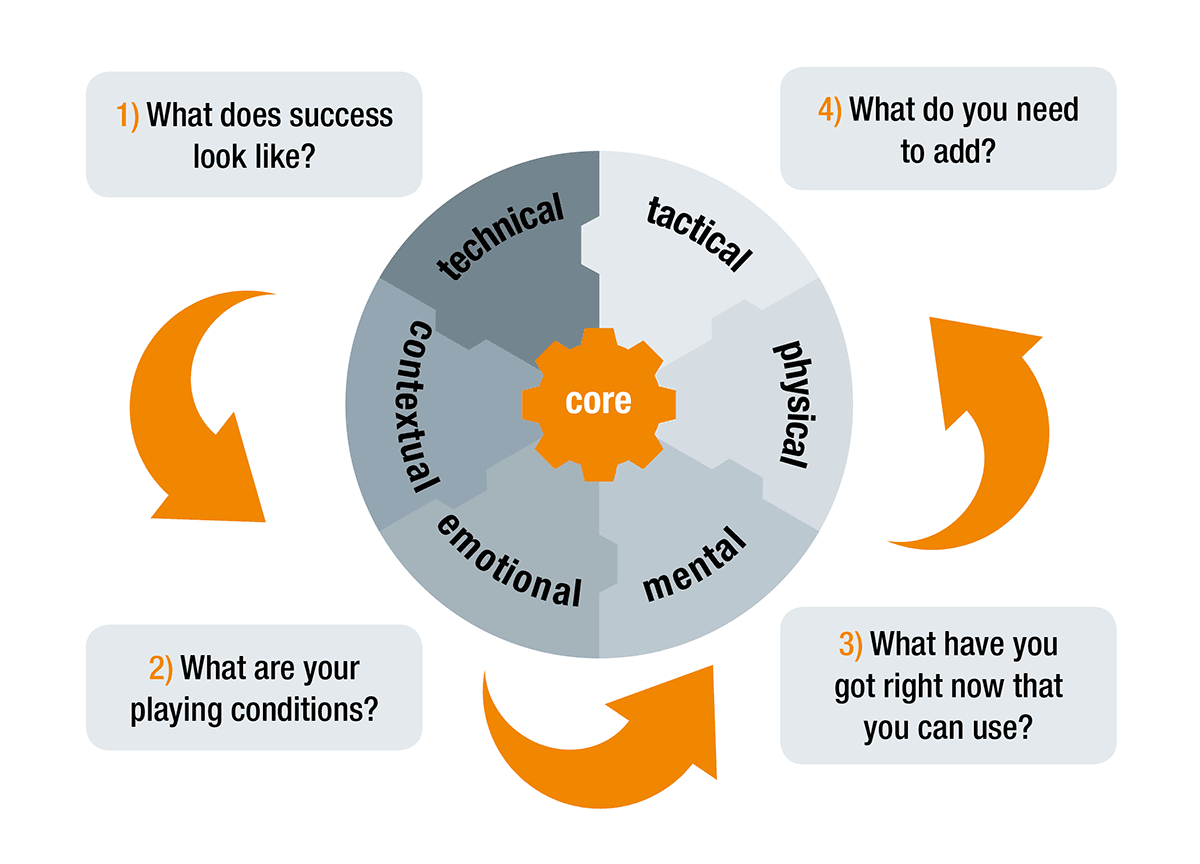

Figure 3: As a coach, cycle round these four questions.

Technical Skills, knowledge and experience – are they bang up to date?

Tactical How confident are you that you can use your knowledge and skills in the right way and at the right time?

Mental Attitude, mindset, confidence and belief – are they where they need to be?

Physical Energy levels – are they fit for purpose?

Emotional Who’s in your support team and do they know?

Contextual Is the physical environment increasing your levels of readiness?

Being obsessed that everybody in the business understands the first two and how they apply to them individually is imperative – trust but verify. Don’t take it for granted that people fully understand until they have demonstrated that they do.

Once the elements are clear the process becomes one of repeatedly using four simple questions, and using the answers to decide what to focus on (Figure 3). These questions are:

- What does success look like?

- What are the playing conditions?

- What have you got right now, that you can use?

- What do you need to add?

Cycling around the four questions will increase control, confidence, and curiosity goals (what if we tried…?), and over time will lead to both mental and physical benefits.

Echoing Dr Sanders, Dr Shambrook stressed the importance of creating open and supportive environments where critical analysis of every element of performance is encouraged and used to determine what needs to be done next – so not so much feedback as feedforward.

Dr Shambrook can be contacted at chriss@planetK2.com.