Value propositions: the sales and marketing interface

18th December 2018 | Simon Kelly

In original research for his Doctor of Business Administration qualification Simon Kelly asked: How do sales and marketing produce business-to-business value propositions?

Background

I became interested in how sales and marketing work together (or not!) to produce value propositions at the turn of the millennium in my role as Marketing Director for BT’s Major Business Division (BTMB). In an increasingly competitive market, in tough economic times, growth was stagnating. The BTMB board felt that marketing and sales were finding it difficult to articulate value that differentiated BT in the eyes of customers in the context of having a product portfolio of over 1,000 products and services.

Salespeople had to cope with product literature coming at them from legions of product managers who were only interested in pushing product features, not customer benefits. Communicating to customers one product at a time confused the customers and got in the way of understanding the customer issues and providing solutions to their business problem. Here we developed an approach to value propositions centred around the customer theme of “business agility”, which enabled the bundling of products and services as agility solutions, delivering excellent results, in both revenue and customer satisfaction.

I left BT in 2002 to pursue a career as a “pracademic” blending a role at Sheffield Business School while developing a consulting business to help B2B marketing and sales teams develop value propositions that resonated with customers and drove growth.

During a spell back in a full-time commercial role between 2010 and 2012 I worked for one of the largest telecommunications companies in the USA with a mandate to move them towards a more customer value-based approach. Here I observed something that I had also witnessed when working with other large organisations through my consultancy: that the product push approach was back masquerading in the clothes of value propositions.

Often “value-propositions” were generated by marketers sitting in rooms remote from customer trying to articulate how their products added value. They were not creating authentic value propositions as they were constructed without any customer or sales team input. At best, they were communicating product advantages (or assumed benefits), not customer benefits as Neil Rackham describes in SPIN. At the same time, researchers Anderson, Narus and Van Rossum (2006) observed that many value propositions were being created as generic all benefits statements that lacked resonance and relevance to customer needs.

I returned to the UK in August 2012 to resume my old combination of Sheffield Business School marketing lecturer and consultancy owner, with a determination to get a better understanding of how sales and marketing worked to produce value propositions.

I reviewed two areas of literature before doing the research which covered sales-marketing interface (SMI) and value propositions.

Sales-marketing interface

SMI literature primarily focused on “The extent to which activities carried out by the two are supportive of each other” (Rouzies, et al. 2005). SMI research has tended to focus on sales and marketing relations as an end in itself. Although no clear definition was provided in the literature, the word interface is used in line with a dictionary definition as: “A point where two systems, subjects, organisations, etc. meet and interact” (Oxford English Dictionary 2015).

Almost all the SMI literature recognised that there was conflict between marketing and sales, most authors portray the two organisations at worst as being “at war” (Kotler et al. 2006), or at best dysfunctional or problematic (Dewsnap & Jobber 2000; Malshe et al. 2016). Differences between marketing and sales have been classified as economic and cultural in nature – here cultural encapsulates cognitive differences (Beverland et al. 2006; Kotler et al. 2006; Snyder et al. 2016). Responses to economic differences are better developed than cultural differences resulting in recommendations such as goal and role alignment (Kezsey & Biemans 2016; Strahle et al. 1996). Little work has taken place to develop cultural and cognitive differences identified a decade ago (Beverland et al. 2006; Homburg & Jensen 2007). There has been little conceptual model development to integrate the economic, cultural and cognitive aspects or to speculate how they may interrelate and have the potential to influence sales and marketing interworking. Overall, the volume and level of debate seems to be in its infancy in relation to academic studies into how the SMI works. There is not yet any apparent level of insight into effective SMI working.

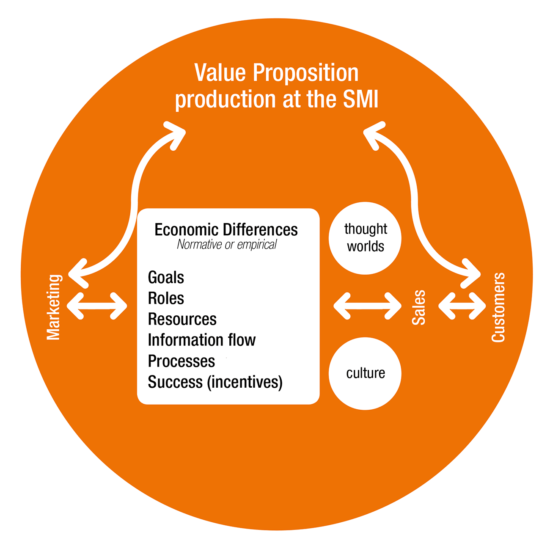

Figure 1: Spaces between sales and marketing for value proposition production.

Sales and marketing were treated as holistic organisations, paying no attention to individual sales and marketing people. The lack of concern for value proposition production in the SMI literature left several questions unanswered, for example: how are value propositions created? What are the respective roles of marketing and sales in developing these? How is the customer engaged in value proposition production?

Value proposition literature

After a rigorous review of value proposition literature Christian Kowalkowski observed:

“The general conclusion is that the ability to communicate a firm’s value propositions strategically and effectively is a new area for the development of competence at the heart of competitive advantage” (Kowalkowski 2011, p.277).

Barnes et al. (2009) describe the evolution of the term “value proposition” as rooted in the 1950s with the notion of the unique selling proposition (USP). This led to the movement in benefit-led selling (Rackham 1988) where sales and marketing teams were coached to move from product features through to describing customer benefits. Only then did it dawn on organisations that a benefit can only be so if it solves a customer problem, a solution to a need. This is when the term value proposition was conceived.

The origination of the term value proposition is credited to McKinsey consultants Bower and Garda (1985) where they discuss the making of promises of satisfaction as part of a marketing-oriented value strategy for business. Since that time the definition of value propositions has remained highly contestable. My preferred definition is: “A value proposition is a promise of expected future value, illustrating that future relevant and distinct benefits will outweigh the total cost of ownership” (Kelly, Johnston, Danheiser 2017 p.30).

The value proposition literature does not pay much regard to the interaction of sales and marketing people working together, and with customers, to create value propositions. The major concern of the VP literature is focused on classifying value propositions into types or in terms of effectiveness (Anderson et al. 2006; Ballatyne et al. 2011), or in relation to marketing theory development (Kowalkowski 2011).

Both bodies of literature look to examine the thing which concerns them, SMI or value propositions, as an “end in itself”. Little consideration is given to how value propositions are produced, and no attention is paid to how the individuals in the SMI work to produce value propositions, a major concern of my thesis.

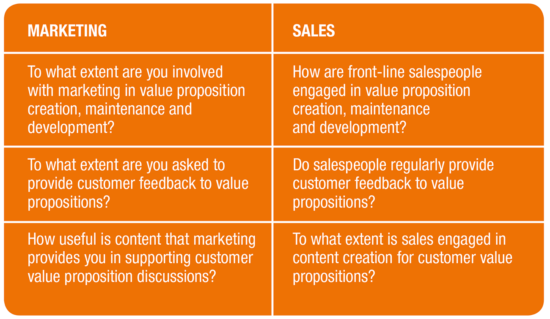

Table 1: Sample interview questions.

Figure 1 shows the “spaces in between sales and marketing” as it relates to value proposition production. Economic factors relating to role and goal alignment were seen as barriers or facilitators for effective alignment as were different measures of success. Thought worlds and cultures are touched upon in the literature in an ad hoc manner with little insight developed into how these influence value proposition production.

Research methodology

I conducted 21 interviews between September 2015 and May 2016 by telephone, Skype or face-to-face. The Interviewees were senior sales and marketing people in B2B organisations chosen because of their experience and tenure, many of them at VP level and above. The interviews, typically lasting an hour, were semi-structured and contained questions to salespeople that mirrored those asked of marketing respondents – some example questions are in Table 1.

Thematic analysis was used to draw out themes from the interview transcripts (Braun and Clarke 2006). This is essentially a more formalised and structured way of interpreting interviews than practitioners intuitively use, which looks for patterns coming out of the interviews. I operated a research philosophy called Critical Realism (Bhaskar 2008) which encourages researchers to look below the surface of what’s being said by interviewees, again something many senior practitioners do naturally. What’s important to say here is that Critical Realism does not accept that it can be proven that x causes y. When human beings are involved, we can look for things, called generative mechanisms, that have the tendency to produce a particular outcome. I was looking to discover what the generative mechanisms were that could help sales and marketing work to produce value propositions more effectively.

Findings

There were three main themes that came out of the interview data: the professional identity of sales and marketing practitioners, the issue of customer contextualisation, and practitioner thought worlds.

Identity

Lots of attention was paid by the interviewees to how they identified themselves in the SMI, and in relation to value proposition development. Five clear aspects of identity stood out:

Aspect 1 – Not a single entity

Practitioners did not regard themselves as being in a function known as marketing or sales. In particular, marketers were at pains to describe themselves in a professional role, for example, Brand and Communications, and rarely spoke of being in the marketing function.

Aspect 2 – Distant versus adjacent

Sales’ view of marketing was heavily influenced by how close or “proximate” they felt marketing were to them. These judgments were based on: whether marketing produced “generic” or “specific” marketing, whether marketing was a central function or “local” to the sales organisation, whether marketing produced work that was customer-centric “outside-in” or product-push “inside-out”. Marketing and sales practitioners viewed product marketers, in a generally derogatory sense, as producing marketing that was all about the product. This was unfavourably compared to industry marketers who produced more “outside-in” marketing where the customer was present and at the forefront of marketing.

Aspect 3 – Customer exposure

How much exposure to customers’ marketers were seen to have was regarded as an important consideration relating to how they were seen by sales.

Aspect 4 – Multi-faceted nature

Marketing and sales practitioners recognised the multi-faceted role of the marketing function where their role in producing value propositions could be influenced by complementary or conflicting activities.

Aspect 5 – Valet to value-add

Marketing practitioners talked about how their identities had evolved over time from the “Golf ball and umbrella marketing” more meaningful roles working closely with sales, for example, Industry Marketing or Account Based Marketing (ABM).

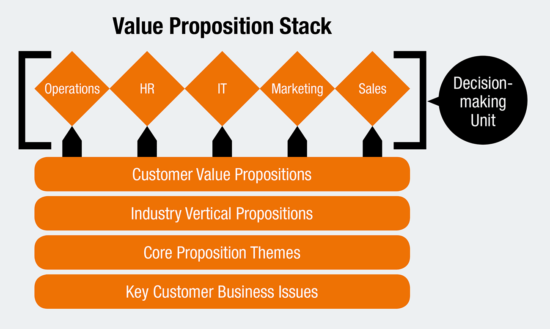

Figure 2: Value Proposition Stack.

Contextualisation

The ability to be able to develop value propositions at several different layers of context was a major theme running through the research. Salespeople were critical of marketers who could not get beyond talking at the “general” – they were looking for help to develop value propositions that resonate at the industry, customer, and individual level.

All the interviewees worked in organisations that split their customers into industry sectors. While it was acknowledged that marketers must come up with “general level” value themes, such as agility, the handover point – typically at the industry value proposition layer between marketing and sales – was problematic. Now the salesperson must develop value propositions relevant for her customer that should align to the themes to help develop the overall company brand. There is often a chasm at this marketing-sales handover point that an SVP of sales insightfully called the “sophistication gap” as often the material that comes from marketing is too generic.

“I think generally speaking there is a sophistication gap and certainly you’ll hear from sales that I need use cases, I need references, I need a translation of your insights into actionable discussions. I think it’s a joint responsibility.”

The Value Proposition Stack was developed, in response to this contextualisation finding (Figure 2), which shows the different layers of context for VPs.

While the Value Proposition Stack provides a framework for value propositions, it does place emphasis on the ability of both sales and marketing to contextualise at each layer of the stack. Dennis, a marketing manager responsible for ABM at a technology company, who was praising the benefits of ABM for alignment around value proposition production when asked “what sets your company apart”, answered: “Nothing, we are in a commodity industry.” A marketer needs to be able to provide context for what sets the company apart at a 5,000-foot level and give sales the tools to develop numeric value propositions at a customer level – “From stratospheric to numeric”, is how I would describe it.

Thought worlds

Finally, what clearly came out of the research was that sales and marketing people think differently; “thought worlds” were made up of five dimensions:

Customer versus product. Salespeople and marketers in roles close to sales, such as Industry marketing, observed that product marketers were driven to get the next product out the door and led with the product.

Respondents also refer to living inside a larger corporate thought world, which could be product-centric. Caila, Vice President of Sales, Global Telco, makes this point: “We go, we’ve got to sell voice, we’ve got to sell data, we’ve got to sell this, and that…. It just might as well have a grocery shop.”

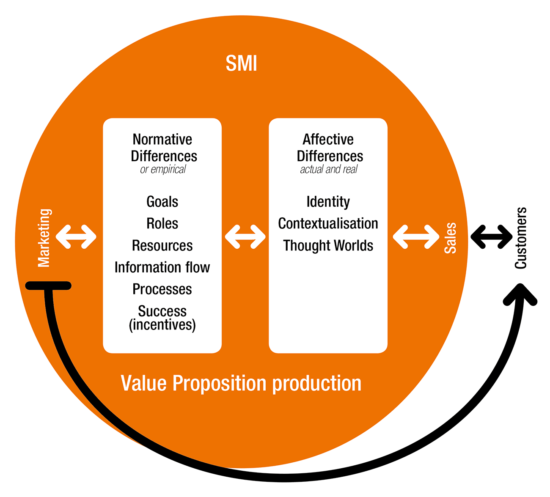

Figure 3: Integrated model of SMI interworking for Value Proposition Development.

Inside-out versus outside-In. When asked to define what a value proposition is, there was a broad variance with product marketers at one end of the continuum and sales leaders at the other. Here are two contrasting views: Althea, Vice President of Marketing at a cable company saw a VP as: “The compelling reason that a customer would be interested in your product; it’s your differentiator.” Caila, provided a much more outside-in view: “Where you really get customers’ attention is completely about understanding what concerns a business or what the next challenges are…. A value proposition is where you can come in, really show you understand that…. It’s a little bit like detective work. You have to find out what’s been going on and then you have to solve for it.”

Short term versus long term. This reflects the tension between sales winning a deal in the short term and marketing’s broader responsibility for longer-term development.

Deal versus market. Even the marketers with roles close to sales had to take a whole Industry or market view which could put them at odds with a sales focus to win an individual deal.

Holistic versus atomistic. Here marketers in roles closer to the customer are much more aligned with sales than other parts of the marketing organisation. Often product marketers get called into deals when the customer is comparing one product with another; their feedback to the organisation can be coloured by this view, as summed up by Saskia, who has had marketing director roles in several industries: “So, value propositions were created mostly by the product team who have had a tiny sliver of interaction with potential customers. So, what they thought the customer cared about was not holistic.”

Integrated model for value proposition development

Drawing my research together with the existing literature led me to construct a framework for sales and marketing interworking for value proposition development which is shown in Figure 3. What this model shows are the types and range of factors that influence the effectiveness of the SMI in producing value propositions. Unless sales and marketing leaders pay attention to the visible and invisible aspects of interaction and the inter-social as well as the process aspects of sales and marketing interaction, the likelihood is that value proposition production will be sub-optimal.

Detailed strategies and recommendations for creating value propositions that are “relevant and distinct” can be found in a book I co-authored: Value-Ology: Aligning Sales and Marketing to shape and deliver profitable customer value propositions (Kelly, Johnston, Danheiser 2017). Ideas about how salespeople can get more connected with customer value to help enhance value propositions will be shared in future editions of the Journal.