Align or die?

31st October 2015 | Simon Kelly

How do we re-engineer the sales and marketing interface for the benefit of our customers?

Just as I sat down to write this article my email pinged. I tried to ignore it as I’d just come back from an excellent “Sales-Mind“ workshop that reminded me of the foolishness of multitasking. Then I saw the title – “Brands failing to align sales and marketing divisions“ – and the relevance justified the short diversion.

Less than 40% of firms believe sales and marketing are aligned with what their customers want.

What I found in the Marketing Week article was no great surprise. A survey by recruitment specialist Randstat found that, despite 80% of UK businesses recognising the benefits of greater alignment between sales and marketing, 40% still have no systems in place to unify the functions. The biggest barriers to integrating a strategy to bring marketing and salespeople closer together included perceived rigid organisation structures (cited by 34%) and corporate culture bias towards sales and marketing roles (26%). Commenting on the results, the managing director Ruth Jacobs, concluded: “British businesses continue to suffer from a seemingly unbridgeable divide between their sales and marketing functions.”

This is not a peculiarly British problem; indeed, a number of recent pieces of business research seem to indicate that this lack of alignment is prevalent. In Frugalnomics (Pisello, 2015) Tom Piselllo points to SiriusDecisions’ research (2014) which found that 32% of salespeople lacked useful or relevant content from marketing. In Aligning Strategy and Sales (Cespedes, 2014) Frank Cespedes reminds us that “Studies indicate that less than 40% of firms believe sales and marketing are aligned with what their customers want”, the very reason for alignment.

So, sales and marketing alignment still appears to be a problem at a time when it matters more than ever. In this omnichannel era when potential buyers get lots of product and company information on-line, Pisello (2015) points out that 67% of buyers have a clear picture of the solution they want before they engage a sales rep (Sirius Decisions 2014). At the same time, 94% of potential customers have disengaged with vendors because they received irrelevant content (Corporate Executive Board research).

Nothing much seems to have changed at the Sales and Marketing Interface (SMI) since the seminal Harvard Business Review article “Ending the war between sales and marketing” (Kotler, Rackham and Kirshnaswamy, 2007), despite the heightened significance of the consequences of misalignment.

Overall, the volume and level of academic debate around SMI working seems to be in its infancy. Studies tend to focus on single issues from which generalisations have been made (Homburg, Jensen and Krohmer, 2008). There is not, as yet, any apparent level of insight into effective SMI working. Here we will focus on four of the themes in the SMI literature that draw out differences between the two functions – these are: economic and goal differences; cultural differences; cognitive or “thought world” differences; and sales “buy-in” to marketing strategy.

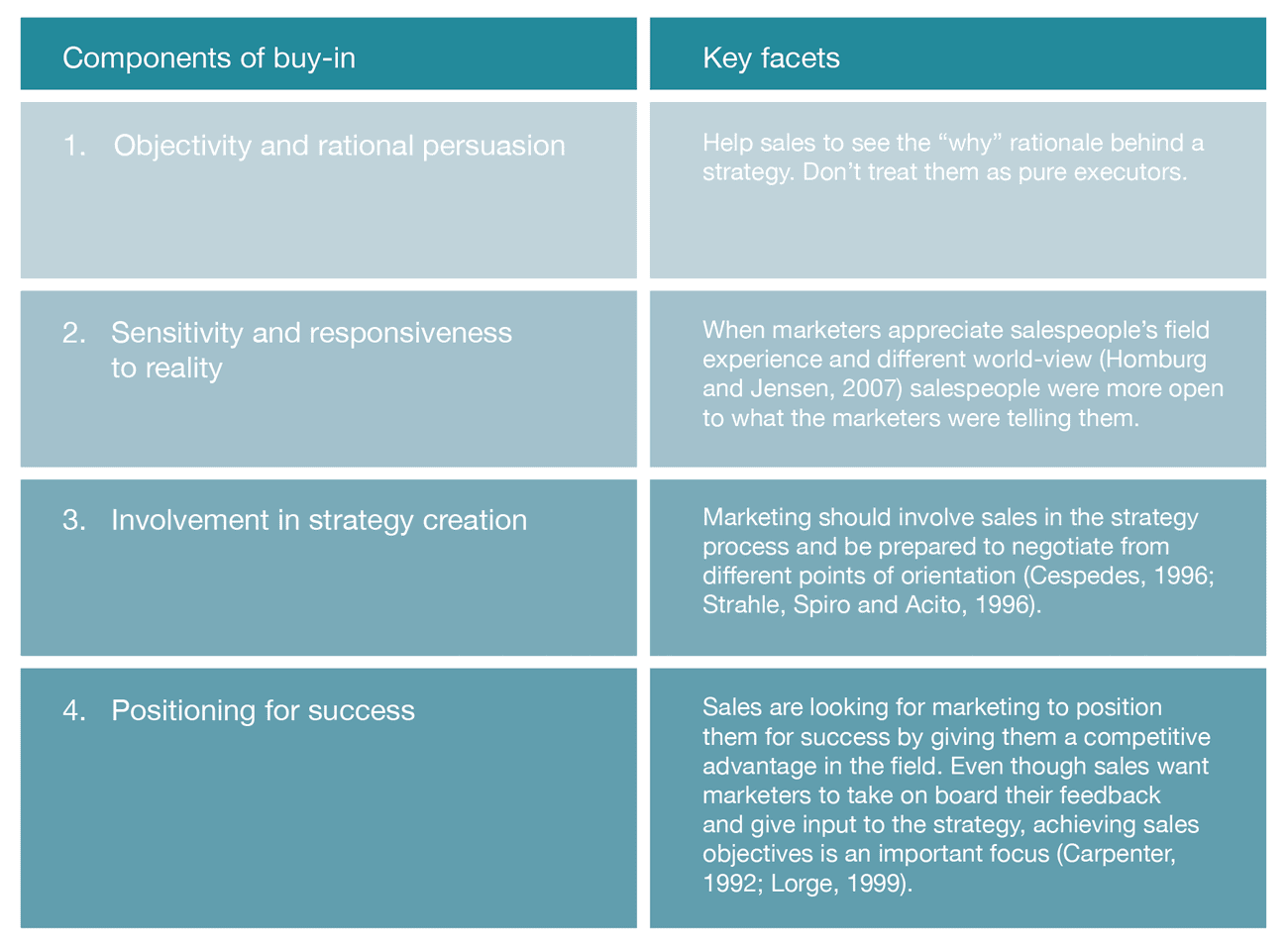

Diagram 1: The four components of sales buy-in

Economic differences

These really begin with budget allocation: with resources scarce, not all marketing and sales activity requests will get fully funded. Kotler, Rackham and Kirshnaswamy (2007) also point to tensions inherent in the marketing mix (4Ps)*. From a price standpoint, marketing sets the list price while sales can go straight to the chief financial officer (CFO) for sign-off on individual bids. With regard to promotion, sales can be critical of where money is spent, and can question the relevance of marketing material provided to them, as we saw in the research earlier. The VP of sales might prefer extra salespeople to money being spent on advertising or brand-building activity.

Goals and incentives can also be at odds. While the sales function tends to be rewarded for hitting sales and revenue targets for a set of customers, marketers may be incentivised for achieving programme goals that don’t tie directly to sales goals: marketers tend to have profit and loss as a key metric, while sales is focused on volume and revenue.

Cultural differences

Studies by Beverland, Steel and Dapiran (2006) examined the question of “cultural frames“ to test if these resulted in tension between marketing and sales. The definition of culture was one that consisted of mental frames by which we approach behaviour.

They identified four cultural frames:

- Valid scope of focus and activity – Sales is focused on a single or small group of customers, while marketers look after a whole market.

- Time-horizons – Sales is interested in short-term immediate customer needs. Marketing is more long-term focused and pays little regard to day-to-day customer problems.

- Valid sources of knowledge – Marketing only see sales as a valid source of short-term, individual customer information; not for anything more strategic.

- Relationship to environment – Sales perceptions and practice identify the importance of reacting to customer requirements; marketing is concerned with driving the marketplace to increase margin and sources of growth.

Bringing this discussion up-to-date Cespedes (2014) cleverly describes marketing and sales as “alone together“. He points out that, because of scope differences, sales will want to customise for an individual customer, which may not suit marketing. Interestingly however, Rouzies and Hulland (2014) found that, where customer concentration is low, sales and marketing can align to support a big-spending customer in a way that may not be beneficial to their organisation. They put this down to a power imbalance that many B2B salespeople will have experienced.

Problems arise due to conflicting priorities or “dialects“, or what is considered to be core activity in daily routines. Over time, these determine “how things are done around here“ leading to “Esperanto silos” (Cespedes 2014).

The challenge is to engage salespeople ‘where the rubber hits the road’; with strategists ‘where the rubber meets the sky’

Different thought worlds – on the same wave-length?

Homburg and Jensen (2007) sought to understand whether differences between the “thought worlds“ displayed by marketing and sales organisations are beneficial or not. They considered how differences in world-view could help or hinder the enactment of marketing and sales decisions. Their investigation revealed that, in general, differences hamper co-operation between marketing and sales, which leads to lower performance. However, some facets of such thought-world differences enhance performance through a direct effect that outweighs the negative effect of quality of co-operation.

There are contradictory views on the nature of thought-world differences found in the management literature. Some have called for similar thought worlds (Donath 1999); others have supported differences, for example, Cespedes (1996): “The solution is not to eliminate differences among these groups.”

Homburg and Jensen (2007) found that different thought worlds can have a positive effect. Competency differences are bad as they adversely affect performance. Differences among interpersonal skills and the knowledge funds of marketing and sales pose an interpretive barrier which gets in the way of optimal decision making.

Sales “buy-in” of marketing strategies

Salespeople are “boundary spanners” between the customer and the organisation. As such, they play a crucial role in ensuring firms implement strategies effectively (Malshe and Sohi, 2009). Where marketing does not involve sales in strategy development, they may view the initiatives as ineffective or irrelevant (Aberdeen Group, 2002; Dewsnap and Jobber, 2000; Kotler, Rackham and Krishnaswamy, 2006; Rouzies et al 2005). This will mean the sales function does not buy into or support the initiatives proposed (Lorge, 1999; Strahle, Shapiro and Acito, 1996; Yandle and Blythe 2000).

Malshe and Sohi (2009) felt that the extant SMI literature had not explored the notion of buy-in. They found that getting sales buy-in consisted of four key components; these are summarized in Diagram 1.

Crucially, the customer does not seem to be getting a coherent story from marketing and sales.

The notion of “buy-in” integrates some of the earlier themes into the four stages proposed by Malshe and Sohi. Cespedes (2014) makes a compelling case for the need to align strategy and sales. The challenge is to engage salespeople “where the rubber hits the road”; with strategists “where the rubber meets the sky”.

Hughes, Le Bon and Malshe (2012) proposed an integrative framework for the SMI. This eight-part framework begins with developing a shared vision and includes: alignment, which requires the ditching of functional silos; processes, to facilitate SMI cooperation; sharing of market information and better knowledge transfer between functions. The other performance levers are decision making, resources and culture (see p62).

From what we can see through research results, it appears that this is much more difficult to achieve in practice. As my old managing director at BT used to say: “It sounds simple, but it ain’t easy.” How do you get alignment? Which shared processes need to be developed? How do you effectively share information? These are all questions practitioners seem to be wrestling with. Crucially, the customer does not seem to be getting a coherent story from marketing and sales.

I have just started my own research to examine how the SMI works towards developing and enhancing value propositions. Hopefully, concentrating on a key output of the sales and marketing relationship will shed some light on these questions. The higher goal is to provide the SMI with some practical advice for better cooperation and performance.

*The classical “4Ps” of marketing are: price, product, promotion and place.