The gift of anxiety

26th July 2021 | Claudia Filsinger and David Britten

Perhaps surprisingly, the nature of anxiety means that it offers an inherent opportunity for personal and professional growth.

In high-value and complex B2B sales, ambitious sales targets and growth plans are common. Typically, sales professionals are measured on outcomes they can control only to a certain extent. As they mature in their career, many develop ways of managing sales pressure and related anxieties.

However, many anxiety-management strategies, often involving other people, have not been available during the pandemic. At the same time, collective anxiety has been heightened due to future uncertainty. This means sales leaders recently found their role had expanded to supporting their teams experiencing increased personal anxiety.

Pre-Covid, the coaching community were already discussing the need for contemporary leaders and professionals to examine their anxieties to operate effectively in an increasingly uncertain world (Einzig, 2017). For example, in highly complex environments, anxiety can help us to ask intelligent questions. The downside can be developing automatic responses to anxiety, like a reflex, in which we get locked in. This might be the case after a bad quarter: even though we may know rationally conditions are much better this time, we might still find ourselves in the grip of anxiety (Claxton, 2016).

Frequently though, anxieties are not acknowledged by individuals which means they take up a disproportionate amount of energy and might be passed on unconsciously to others. How much of an issue this is depends on an individual’s propensity to anxiety but also their career stage. New employees, first-time leaders and junior sales professionals, for example, are focussed on proving themselves and are unlikely to acknowledge their anxiety publicly.

High propensity to anxiety can lead to individuals being prone to soak up anxieties that float around in their context. These can be “the elephant in the room”: for example, anxieties of colleagues or even customers that are subconsciously noticed but not acknowledged.

Frequently, anxieties are not acknowledged by individuals, which means they take up a disproportionate amount of energy and might be passed on unconsciously to others.

Self-coaching questions that take the edge off anxiety by exposing unhelpful thinking patterns such as black-and-white thinking and catastrophising are almost common knowledge. However, this article takes a fresh approach by looking at anxiety not as something wholly negative that is to be managed and avoided. We offer an in-depth exploration of the nature of anxiety, and the paradox that this painful experience offers an inherent opportunity: it’s ultimately a gift that can result in personal and professional growth.

What is anxiety?

While there are many different ways of thinking about anxiety, we have found the ideas of existential thinkers such as Paul Tillich and Rollo May helpful, in two ways. They allow us to distinguish between different types of anxiety. They also enable us to see the potentially life-enhancing lessons that we can draw from this sometimes deeply unpleasant experience.

The first point to note is the key distinction that thinkers have made between anxiety and fear. Fear always has an object: meaning it is always about something specific experienced as a threat. This threat might be physical, in the form of illness, violence or even dying; it might be emotional or psychological, as in the form of rejection by, or loss of, people we care about, such as friends, peers and leaders; or it might be (in the broadest sense) spiritual, involving a threat to values that we hold dear, for example when organisational values conflict with personal convictions.

Because it has an object, fear can be addressed: we can marshal our courage and resources in confronting its challenges, or we can run away. This is not the case with anxiety, because anxiety itself, as opposed to its expression in particular fears, doesn’t have an object. It is this absence of anything to fight against or flee from, this sense of being gripped by something horribly real yet also shape-shifting and intangible like a fog, that makes pronounced anxiety such an unpleasant and potentially terrifying experience.

Three forms of anxiety

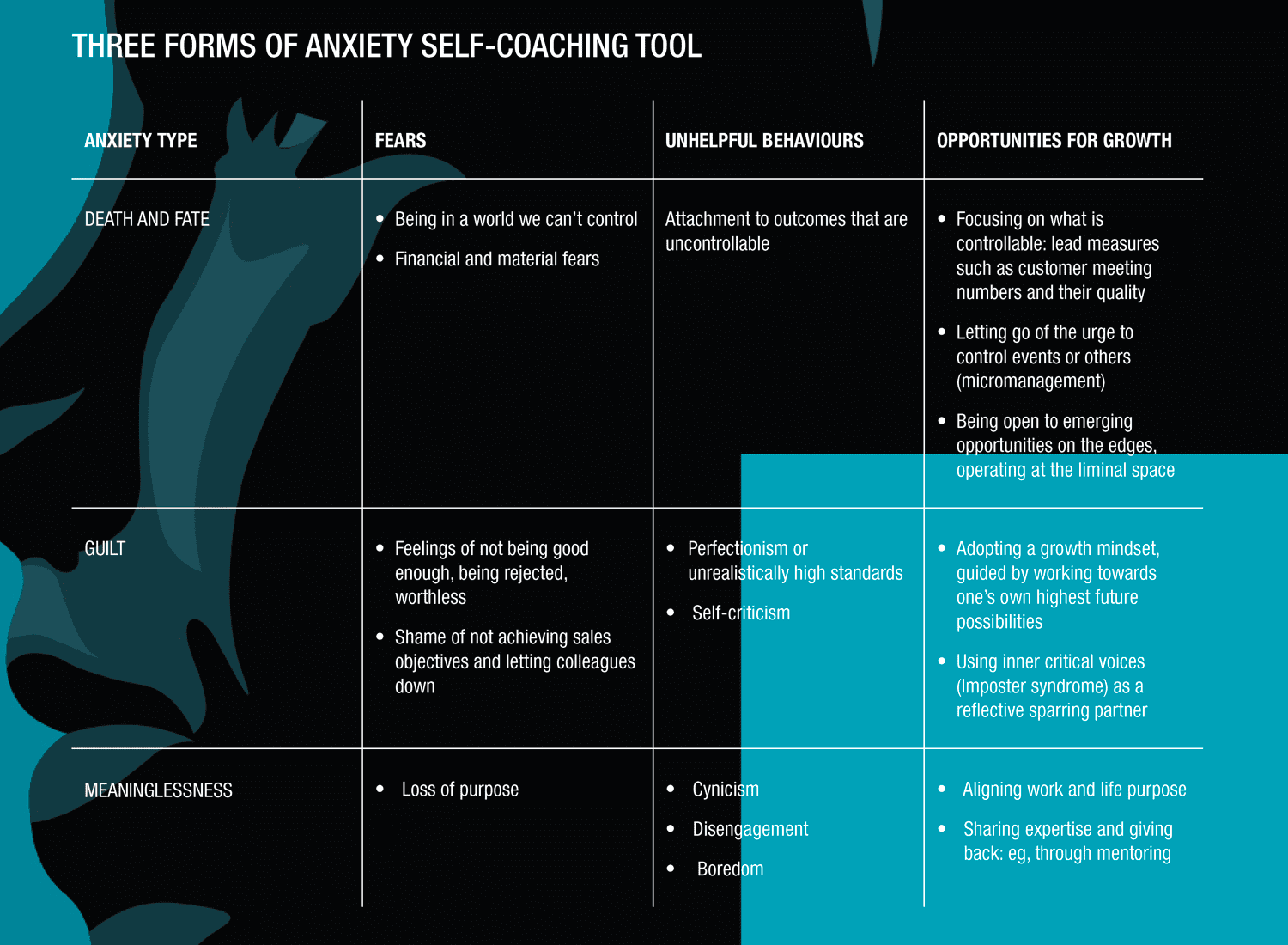

It would be more accurate to say that anxiety does have an object, but this object is nothingness, or as Tillich puts it, “non-being”. For Tillich, “it is the anxiety of not being able to preserve one’s own being that underlies every fear and is the frightening element in it”. Non-being, and its related anxiety, has three corresponding forms: death and fate, guilt, and meaninglessness. Careful analysis will reveal that one or more of these anxieties always underlies our specific fears (Figure 1).

Consider the prospect of losing one’s job. This might raise fears about material security, about a loss of esteem from others or oneself, and about a loss of purpose. Fears about material security are most likely to relate ultimately to anxiety about death, our intuitive awareness of our needs and vulnerabilities as living organisms, and the fact that our lives are ultimately governed by forces we can never hope to fully control. Fears about loss of esteem are probably an expression of the anxiety of guilt, the horrible experience of feeling bad and worthless. Fears about a loss of purpose have their roots in the anxiety that life has no ultimate meaning, that it is, in the words of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing”.

It is tempting to respond to anxiety by avoiding it or treating it as a problem to be managed, and indeed there are times when it might be necessary to use coping strategies to get us through a crisis. However, attempts to deny or eradicate anxiety can have the effect of feeding rather than satisfying its demands. Perhaps the most obvious symptom of such an attitude is perfectionism, which, like more serious forms of obsessive-compulsive thought and behaviour, is usually an expression of the anxiety of guilt.

Attempts to deny or eradicate anxiety can have the effect of feeding rather than satisfying its demands.

Persistent anxiety is generally a sign that we’re avoiding something, that we’re trying to block from awareness one or more of the forms of non-being mentioned above. In doing this, we’re narrowing the compass of our existence in order to avoid confronting our all-too-human limitations. Effective and authentic living in the medium-to-long term requires us to acknowledge – not just intellectually, but, to borrow a phrase from existential psychotherapist Irvin Yalom, “in the sockets of our being” – that death, guilt and the quest for meaning are simply givens of our existence.

The opportunity of anxiety

This is where Rollo May’s ideas are particularly helpful. May suggested that, unpleasant though it is, anxiety is a sign of potential growth. We grow as people by developing the ability to tolerate the feelings of helplessness that anxiety can provoke. If we can learn to listen to our anxiety, rather than blocking it out or treating it as a software bug in need of fixing, we can heed its message for our lives and find ways to transform the shape-shifting nothingness into challenges to address. In this way, we can become fuller versions of ourselves.

Therapists have observed that people who are curious about their anxiety and explore what that “something” is within them that is anxious are more able to change (Gendlin, 2003).

For example, acknowledging the reality of death can help us to better appreciate the scarcity-value of our lives, to use our time well and to be grateful for the gift of existence. Recognising our guilt and shortcomings can not only free us from various forms of perfectionism and other more or less trivial concerns; it can also enhance our compassion for others, and give us the permission and courage to take on more substantial and challenging projects. Tolerating the murky ambiguity of existence rather than seeking to make perfect sense of things can better equip us to confront the complexities of 21st century life.

In summary, the imposed changes caused by Covid have put many people in closer touch with their anxieties, and deeper levels of compassions have been extended to colleagues. Many professionals report increased clarity about their purpose. We have shown how anxiety can offer a gift for growth and Figure 1 can be used as a self-coaching tool to identify opportunities for growth. If you are experiencing anxiety at a level that impacts your health, we recommend you contact your doctor or your organisation’s employee-assistance programme which typically offers anonymous counselling services.

References

Claxton, G (2016), Intelligence in the Flesh: Why your mind needs your body much more than it thinks, Yale University Press.

Einzig, H (2017), The Future of Coaching: Vision, Leadership and Responsibility in a Transforming World, Routledge. Gendlin, E (2003), Focusing, Rider.

May, R (1996), The Meaning of Anxiety, W.W. Norton & Company.

Tillich, P (1980), The Courage To Be, Yale Univeristy Press.

Yalom, I (2013), Love’s Executioner and Other Tales of Psychotherapy, Penguin.