Improved leadership communication

9th November 2020 | Waldemar Adams

How storytelling can help bridge the gap between management and teams.

“1In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.

2The earth was without form and void, and darkness was over the face of the deep.

3And God said, “Let there be light,” and there was light.

4And God saw that the light was good.”

Genesis, First Book of Moses

Day 1

Since the dawn of mankind, we have been telling stories. When we started to rise from the African savanna, the tribes of ancient hunters came together around their campfires, and the elders and shamans told their stories. In the darkness of the night surrounding them, in the darkness of understanding and knowledge, they gave light and warmth to hearts and souls of their people. They told stories about the stars above and the animals on the ground, about gods and ghosts, about what was good and bad. They told stories which explained life, gave purpose, set direction and guidance. Some of those stories became our shared myths and they shaped the archetypes of stories (Vonnegut 1995) we also use today as they are universal to us (Reagan et al 2016). We are a species hard-wired for telling and listening to stories (Nossel 2018). Stories are an essential aspect of our species, and research indicates that the ability to tell stories is the one core element which differentiates us from other animals, mammals or apes (Gillespie, Cornish 2009; Stone et al 2012).

Stories are the tinder to create the intersubjective reality (Harari 2015) which defines everything that we believe in, and what we call “common sense”: values and morals, nations and teams, companies and money. A $100-dollar bill only has its value because we all believe in the same story of its value (Harari 2015). This bill is made up of cotton and linen and printed with colors, and costs 14.2 cents to produce (Federal Reserve 2018). The story is what makes the fundamental difference.

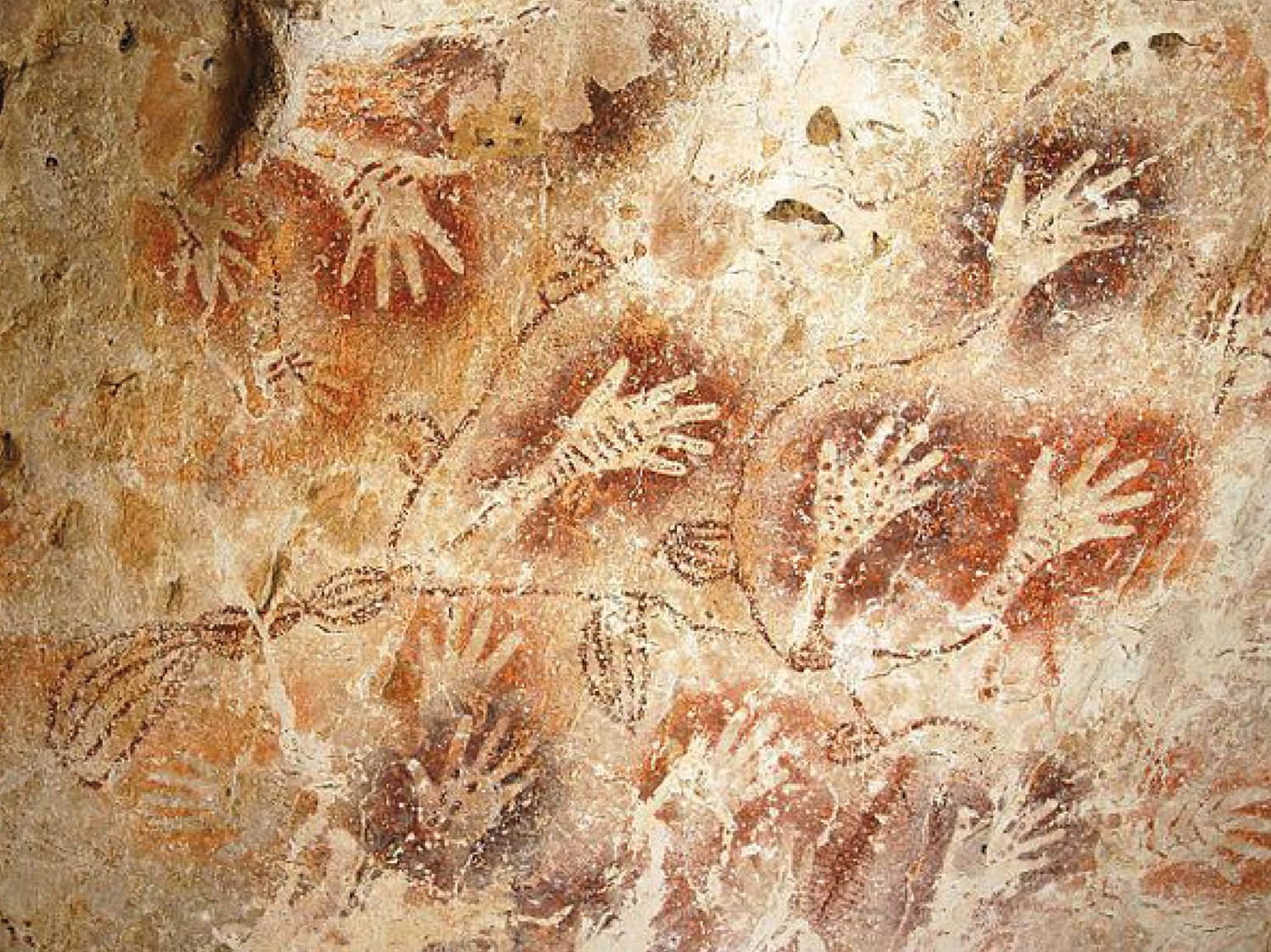

Since the dawn of mankind, we have not only told stories, we also have written them down. Next to the narrator, there is the writer or as we may call them today, painter of stories. We can still “read” them because there are myriads of cave paintings we discovered on every continent, the earliest dated 60,000-40,000 years BP. This truly is a “long-distance call” through time. Stories help us to understand what we are and tell us the purpose of what we are doing. They build an emotional connection with the people who listen or read, and allow us to reach out to the hand of our ancestors from a world aeons ago.

Today

Writing these lines, I realized that I have been fascinated by stories all my life. I love a good story, in a book, watching a movie or listening to someone telling one. From cave paintings to cuneiform, to books and the Bible and, in our day-to-day life with emails, YouTube and TED, stories remain the glue between the generations and build a bond between narrators and audience, writers with readers, and leaders with their followers. This extends to my teams in business life. I love to tell stories to the people in my team, to my mentees and to our customers when I am on stage. Communication is the basis of everything in an organization and the connection between us all. Communication can be the start of success and change or the beginning of confusion and failure.

Tomorrow

Homo sapiens, the “wise man” is what we all are as a species. On the level of individuals, this turns into “Homo narrans” (Auvinen et al 2013), the “storytelling man”. We are biological machines and genetic algorithms (Harari 2015); our brains are wired for stories (Nossel 2018). We need (to continue) to use the ancient art and science of storytelling also within our business communication. Because business success is most often measured by numbers, we need to consider that we, humans, are the ones doing the job and we need more than numbers; we also need stories and not only 0s and 1s like a robot. Moreover, the use of a good, meaningful story it is neither outdated nor old-fashioned; it is mission-critical (Drake 2007). With the findings of my research, I want to pass that knowledge to others in my company to change the way leaders communicate with their teams.

Even as we are communicating all the time, even if we are surrounded by communication all day, it is neither easy nor simple: “The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place,” according to Whyte (1950). From my experience, I believe he is right. I want to better understand and research how leaders use storytelling in their communication and also the advantages and disadvantages there are in doing so. I invite you to join me on my journey to discover the secrets of successful leadership communication in a sales organization.

We as individuals are all Homo narrans (Auvinen et al 2013). As a consequence, storytelling has been central to the human experience for so many millennia that it has become hardwired into our brains (Nossel 2018). By harnessing this effect in business life, storytelling helps to improve leadership communications in organizations (Luhn 2015). However, further research is needed to better understand the cultural differences and how to handle them within a global organization (like SAP).

Methodology

Right from the start, I had to make a decision to use a quantitative or qualitative research approach. From my past research, I was using action research (McNiff 2010) and intended also to use it for this research project. However, as this is about living in and observing a culture I decided to use ethnography (Walford 2009) as the leading methodology because it exactly describes my situation working and “living” in the culture I observe. Ethnography fits to a large extent my research theme and approach, me being an inside researcher at SAP. For the text analysis during my data collection phase I used hermeneutics (Mantzavinos 2016). This is to collect some information about the texts itself, number of words, topics mentioned, the sentiment of the message and narrative.

Gadamer (1975) stated that prejudice is foremost a neutral element of our understanding and not by default negative. Prejudices, in the sense of “expectations” about the thing we want to understand, are unavoidable. He observes that “we can never step outside of our tradition – all we can do is try to understand it.” Gadamer (1975:309). Being aware of this and using critical self-reflection at all stages of the research should help to mitigate prejudice.

I used ethnography to observe the SAP communication culture and the people who work and live in this organization – in particular for running my one-to-one semi-structured interviews. I used modern hermeneutics and narrative inquiry (Clandinin 2008) for the analysis. Narrative inquiry utilizes field texts (for example stories, notes, autobiography, newsletters, interviews) as the base of its research to analyze and understand how people use narratives to create meaning in their lives.

I found it interesting that auto-ethnography analysis “shares the storytelling features with other genres of self-narrative but transcends mere narration of self to engage in cultural analysis and interpretation” (Chang 2016:38). I was also inspired by Belk (2014) who posits that an effective way to share “ethnographic insights to business is through telling stories” (Belk 2014:553). As a consequence, I used the principles of storytelling to present the findings of my research about communication by using storytelling for (sales) leaders.

The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.

I followed Covey’s advice: “Seek first to understand, then to be understood” (1989). Therefore, I started with an assessment of the existing leadership communication with a focus on the western European culture (SAP’s regions EMEA North, South and MEE). I collected quantitative data on leadership communication in the named regions and for two global organizations: the Global Customer Organization (GCO, our sales teams) and also our CEO office.

For further analysis of this information stream I used (modern) hermeneutics combined with narrative inquiry. How “long” was the communication? How many words have been used? What was the sentiment of the message, was it positive (eg, achievements), negative (eg, reduction of costs) or neutral, which topics have been selected (eg, announcements, vision statement, goals)? Also, I wanted to track the style: was it text only, did it used artwork or also modern media like videos or even surveys?

The core of my data collection was semi-structured interviews. This is all about qualitative data. The people I intended to work with were salespeople, sales-support teams and sales leaders in the given regions as they are the receivers and senders of communication. For the interviews, I prepared a set of standardized questions, which allowed me to get a repeatable form for interviews which could easily scale and allow better comparison of the feedback.

To better address the qualitative aspect of my research methodology I did not use a fully structured interview schema to give space for open communication and to get also feedback in areas that I had not considered before.

I raised the two core questions for my research:

- What does a (sales) leader need to know about effective communication to drive business success?

- How do we know communication took place, worked as intended and was meaningful?

As my focus was on the “what” (message, context) and “how” (syntax, semantics) of successful communication, I started to analyze first the leadership communication at SAP.

Written communications

I intended to cover both the regional leaders and also the communication of the leadership one level up in our corporate hierarchy, at board level. I also decided to place an emphasis on written communication because this is what happens most in our organization and many other sales organizations as well.

There are not many events or situations when our regional and global leaders speak to their sales teams in person. This is usually limited to our annual sales kick-off meeting, the FKOM, and a few “all-hands” video-conferences or calls. Most of how an individual salesperson “sees” his or her leadership is through email communication. This makes it the main medium through which people in our organization view our leaders. And for the leaders, this is their opportunity to set expectations, and to give direction and orientation.

I analyzed our leadership email communication among the selected regions and global entities. I also decided to focus on those from 2019, that were sent to the field by using the relevant regional or global distribution lists.

When I was searching for “why” the stories were missing, I received interesting feedback, clearly indicating that the leaders are the blocking element.

Self-reflection

As an inside researcher living in the culture of SAP, I also had an opinion on leadership communication and I asked myself the same questions, interviewing myself. This helped me to sharpen my point of view. It was also very enlightening to observe the similarities and differences between my assumptions and interpretation of the emails sent versus the people I interviewed. This self-reflection enhanced my empathy and understanding of the participants and their motivation and different perceptions, reading the same emails. I observed very clearly that there is more than one truth or meaning.

I wanted to have a broad mix of different people to talk to as participants of my research. I tried to balance the number of people per region, their age, and gender to get, what I felt, a solid base for feedback. I decided to run the interviews with 13 people to have a reasonable size for a sample group. I selected three from each region and two from each of the two global organizations, seven of them male and six of them female, and also of different age ranges and roles.

For each a face-to-face interview I reserved one hour, because I wanted to make sure that there was enough time to have a rich conversation. For interviews by phone, I scheduled 45 minutes as calls are usually straightforward as there is less time and no opportunity to look at each other, pause, or to react to an observation you made as an interviewer about the person you talk to. This is all verbal.

Data analysis

One of the first conclusions I was able to make was that all of the people I approached agreed to join the interviews. Furthermore, all the people interviewed showed interest into the topic, my interpretation was that leadership communication is an important aspect of their business life and when I validated this assumption with my appreciative interview questions, they also clearly confirmed it.

Another interesting finding was that almost all participants have not been happy with the existing communication from their leaders. What I also discovered from my analysis is that the middle-management seem to have different expectations of leadership communication. They are like a “man in the middle”, both having a manager and also being a manager of their teams.

I used thematic analysis to help structure my analysis and articulate my findings. To provide an answer to one of my research questions…

What does a (sales) leader need to know about effective communication to drive business success?

… I distilled the following six core themes from my research.

1. Relevance: Leadership communication is not optional

One of the insights from the interviews is that people like to “hear, what their leaders have to say”. In absence of a regular, direct interaction and communication channel to their leaders, to “hear” your leader usually translates into reading emails – occasionally also with embedded videos with the advantage of really listening to the leader’s voice.

Those communications by telling stories are one of the most effective ways for leaders to connect with their teams and the content they want to convey. The purpose of this connection is to help the employees gain the knowledge to become more productive and to bring about purposeful change (Nuriddin 2018).

“I want to have more communication which is meaningful and explains situations, not more newsletters.” Male team lead.

“I want to have more communication which is meaningful and explains situations, not more newsletters.” Male team lead.

2. Frequency: build the right cadence

From my personal experience, I can clearly state that every missed communication is a missed opportunity to build a connection. From my interview analysis, and also by overlaying the statistical analysis of the leadership communication, I concluded that leadership communication needs to take place on a regular base. It seems that people appreciate a healthy cadence with at least a communication once a quarter or linked to an important event.

It is also important that leaders are supported by communications specialists, in particular those for whom regular communication to their teams is not on their list of main activities. It needs a person (or plan and discipline) to do it regularly.

“She (the leader) is not visible to us at all – only with customers.” Male manager.

Regular communication to be “visible” to your teams is important, even more so if an unforeseen event happens. People like to understand what it means for them.

Quarterly communication seems to be a good cadence, but there is a catch to that. A message “once a quarter” when this is the only or obvious reason can cause an issue with the value and relevance of a message.

3. Purpose: why should people care if there is no value

A strong pattern in the feedback is that people do not want to get an email only because it is the start of the quarter. This is perceived as a newsletter but not as a “real” leadership communication. A newsletter and regular (for instance, quarterly) communication are seen as created by a communications person or someone from the leader’s staff, but not as a true statement from the leader – and so are not perceived as authentic.

“I get the email each quarter start but not when something happens (acquisition) and I need to know what is going on.” Male manager.

Leadership communication should come regularly but not for the reason that a certain period has finished. There are better reasons: to inform, to give guidance, to react and inform on events, and to build trust.

4. Stories are an important skill for communication

Storytelling is an important skill for communication as people remember stories better than only facts or messages with no context. That has been described for example by Drake (2007) and Robinson (2005) and is in sync with my research findings. For the relatively few communications with a storyline, participants were able to almost fully recall what had happened. When I was searching for “why” the stories were missing, I received interesting feedback, clearly indicating that the leaders are the blocking element.

“I give recommendations using story elements but very often they want to do it (their communication) as fact-only. They do not want to take a risk.” Female, Global Communication.

I want to create a situation whereby sales leaders at SAP understand and value their target audience – whether this be employees or customers – and motivate them to tell a story that creates a context for that audience and a narrative that sticks.

Luhn stated that “people do not remember what you said but how you make them feel” (2017) which is a perfect match for the feedback I received during my interviews. When I asked the participants about the best leadership communication they remembered, I was able to observe that, just by thinking about prior leadership communication they liked, this triggered positive feelings and emotions about the given leader.

5. Authenticity: Tell your team what you want to say

It is a typical ability of us as human beings, as a social species, to be able to “read faces”, to interpret body language – and we apply the same principles with the written form of communications. This makes it even more important to be clear and authentic in the message. The interview analysis shows a clear trend that the participants are able to recognize when there is a discrepancy between the message in the communication and the awareness they have about the leader. If this is not in sync it always negatively impacts the perception of this leader. In embedded videos (see interview quote below) people can easily spot the subtle signals showing in their faces and interpret them. For written text, it is comparable to the extent that people easily spot if the message is plain data or has no deeper reason.

“When we saw the first video in the email (speaking to us) it blew us away. Now it has become a habit and you see he did this in five minutes between two meetings.” Male manager.

Often leaders (and other people) are worried that, when they reveal themselves in a story, people in their teams might lose respect for them. In fact, the exact opposite tends to happen. People usually respond positively to signals of authenticity and vulnerability (Nurridin 2018). “Get clear on what you are relentlessly pursuing, and you will know the true nature of your brand and authentic mission as an organization.” (Drake, Lanhan 2017:40). A recognition of authenticity is therefore amongst the main pillars to build trust.

As a social species, we are able to “read faces”, to interpret body language – and we apply the same principles with the written form of communication. This makes it even more important to be clear and authentic in the message.

Trust is the consequence of the themes above and the ultimate social currency

Good communication requires first to build a level of trust with the people involved and is indispensable for a good collaboration (Parkin 2004). The trust of a leader is established by disclosing sensitive and relevant information to the people in their teams with two effects: at first to be treated as trustworthy and second, those people to trust the leader. (Auvinen et al 2013).

“Ideally my leaders give me information up front because I need it to explain to my people. I do not only need facts; I need answers.” Female manager.

I agree with Auvinen et al when they stated that “trust is built among followers at all levels and trustworthy managerial behaviour is actualized in leadership behaviour and communication” (2013).

Speed of light

The speed of light is the fastest speed in the known universe. To the same extent stories are the fastest way to trigger emotions and to impact mindsets. Stories create emotions (Luhn 2018) that tie strong bonds in our brains; they build a bridge which helps us to make a connection. By listening to stories, we do not just understand rationally but “feel” emotionally why a piece of information is important and relevant for us (Robertson 2017). When we spot a story even our brain chemistry starts changing and we switch modes. As a species we are hardwired for stories (Nossel 2018). Neglecting that “is not smart but only makes it hard”. I actually heard this statement during a face-to-face interview (female, Global Communication), and I believe it makes perfect sense.

Magnifying glass

This leads to the second question I wanted to answer with my research:

How do we know communication took place, worked as intended and was meaningful?

The best possible answer sounds very simple but with many good ideas, simplicity is king. One of the results from my interviews is that people like to be asked for their opinion.

“I may have been asked me only once, what kind of information I would like to get or not.” Female manager.

SAP invested in the acquisition of Qualtrics in October 2019. At stated in SAP News, “By collecting experience data at every meaningful touchpoint, you can analyze and understand experience gaps – and determine what to do about them.” I will ask to use this SAP Qualtrics technology to do exactly what it is designed for: to better understand the feelings of our employees about our leadership communication and why things inside and outside of SAP happening. This should mitigate the risk that, as an organization, we listen too much to the few with the loudest voices, and give the silent majority a chance to raise their voices as well by giving feedback through a survey. Over time this will help us to turn ourselves into a better, storytelling organization (Drake, Lanahan 2007).

Recommendations and conclusion

My research was my lantern to search for an honest, authentic leader. I wanted to uncover what role the use of stories in writing (such as emails) can play in successful leadership communication, to make this more meaningful and inspirational.

Let there be stories!

Since the dawn of mankind tribes of hunter-gatherers came together around their campfires where their elders and leaders told stories about the meaning of life and about purpose and reason. Today, those campfires have turned into the spotlights around the stages and podiums our business leaders are standing on to tell stories that provide meaning and purpose of the business life. They create an intersubjective reality (Harari 2015), an “agreement” that makes us all believe in the same things, such as the purpose of our company, the reason why we need to work and what to do next. Usually, this is limited to the range of influence, the people onsite and an audience of customers or partners, but not necessarily for internal teams and employees.

There is another blurred but constant light that shines from the screens and displays of our monitors and smartphones. These are the places where employees mingle virtually to listen to their leader’s voice via a constant stream of emails. It needs a spark to make this type of communication shine and to be distinguishable from ordinary emails or spam. This communication needs to enlighten all of us “readers” to tell us the meaning of business life, the reason for the change and the purpose of our jobs. The narrative elements of the classic fairy tales can help us all to find meaning for our life (Bettelheim 2010). Similarly, storytelling in leadership communication can also help adults understand how to “live” successfully in organizations and to find meaning in their work.

Light at the tunnel’s end – what’s next?

During my research journey I came across known territories, I discovered unforeseen new vistas and filled my whitespace as well. I also had experiences with déjà vu. And I had a vision and idea of what to do next. Unfortunately, as with any good story, the hero doesn’t just walk up to the dragon, chop of its head and marry the princess, and then they live happily ever after. There are also risks and challenges lurking maybe just around the next bend in the long and winding road.

I have already started to engage with people in our communications team, started to discuss my findings with the learning organization, and I will also inform the Global COO of our sales organization. Beyond that, we could even extend the reach of my findings on improved leadership communication to the other four of our seven regions. But “we can only change things when we change the paradigms” (Covey 1989). Therefore, I also see a cat and mouse situation… whereby the mouse represents collaboration and opportunity but the cat eats the mouse doing what it always does as “this is the way of the world, you see”. That is the risk that can literally kill the opportunity.

Today there is potential for a renaissance, a rediscovery of the ancient art of storytelling not limited to children’s entertainment or for readers of novels but for helping leaders, helping all kind of different people in a cold, metrics-driven, results-measuring, shareholder-value-increasing culture of a sales organization to better communicate with each other.

We now need to turn and start to look inside our company and “treat employees as you would treat your best customers” (Covey 1989:24). Such a practice would include without doubt an investment in crafting meaningful communication that also extends to the people within the organization

Therefore, I will need courage to “change the system” (Bridges 2009) and at first work with my colleagues to embed the principles of storytelling in communication in the leadership training offerings.

The potential improvement of applying my findings also highlights a possible weakness: as humans we have a “resistance to change as a natural reaction to a disruption in expectations as well as feeling a loss of control” (Conner 2012). It is one thing to motivate or tell people what to do or to improve and a totally different thing to convince them and to make them change. I want to refer to what Argyris (2008) stated: “People often profess to be open to … new learning, but their actions suggest a very different set of governing values”. There is the risk that people do not want to move, they will stay where they are, and the cat will eat the mouse. I believe that leading by example with leaders showing interest in and listening to the people will help to mitigate this risk.

And finally…

I hope that you broadly agree with my conclusions them. And if you do not, I would be interested in listening to your story. You can reach me by email at waldemar.adams@email.de