Does ethical compliance really make salespeople ethical?

29th November 2016 | Dr Philip Squire, Mark W Johnston and Ian Helps

Pressure on the sales function has placed the salesperson in the uncomfortable position of dealing with complex, unrelenting ethical dilemmas on an almost daily basis.

The sales department has never been more important to the organization. Given clearly established metrics and direct revenue contributions that connect to financial performance, coupled with an essential role in creating customer value, it is easy to understand why sales has overtaken the marketing department as the primary customer-facing function in many companies (Homburg et al, 2015).

At the same time, pressure on the sales function from a variety of sources – customers, management, competitors and others – has put the salesperson in the uncomfortable position of dealing with complex, unrelenting ethical dilemmas on an almost daily basis. To be sure, salespeople have contributed to the problem by focusing on short-term goals and often placing their own self-interest ahead of the company and the customer. The increased importance of the sales function has led managers to consider the potential damage to the company’s short- and long-term performance goals created by the unethical salesperson (or department) operating outside established company guidelines and protocols.

Companies can demonstrate high levels of ‘compliance’ but the actual impact on ethical decision making and behavior is minimal

Corporate scandals

Beyond sales there has been a profound, long-term shift in ethical business practices dating back to the corporate scandals in the United States and Europe more than a decade ago. Initially defined by societal concern then through legislation, companies are now encouraged – even required – to develop and maintain ethical standards. The standards take many forms such as “codes of ethics” or “codes of conduct” but are designed to convey the basic ethical values of the firm as well as define what is and, even more importantly, what is not acceptable behavior throughout the organization.

Research suggests that ethics programs play an important role in conveying the organization’s history, culture and essential values (Ferrell, Fraedrich, Ferrell, 2015) and, when company ethical values are not communicated to employees, they are more likely to make decisions using their own self-interest as the benchmark rather than consider the best interests of the company.

The process of developing a company’s ethical standards usually involves broad input from across the company but is directed and ultimately defined by the board of directors and senior management. For the most part, the goal of the process is to develop broad ethical values and standards for the entire organization rather than focus on the unique challenges of a specific job function such as sales.

Enforcement of the ethical standards is frequently relegated to compliance programs often managed by centralized departments such as HR or Legal. Research reports that over 75% of all ethics and compliance programs are managed from a centralized function rather than localized departmental control (Deloitte and Compliance Week, 2013). The reasons for centralizing the management of compliance programs are consistency of message and risk mitigation.

In some business functions such as finance, compliance certification is not only encouraged but required. However, in most of the organization the compliance program serves more to satisfy regulatory or legal requirements that foster actual ethical decision making and behavior (Biskup, 2014). Companies can demonstrate high levels of “compliance” but the actual impact on ethical decision making and behavior is minimal.

Indeed, it can be argued that the focus on compliance rather than ethical sales decision making can make it very difficult for the salesperson to effectively perform his or her job. It prioritizes compliance over the value-creation sales model.

Sales call

Consider the example below: it is a summary of a short phone call from a telecom sales department, which highlights the limitations of compliance-led sales conversations (call received on a mobile phone).

S – Good morning this is xx calling from telco x. I see that you qualify for an upgrade on your phone; are you interested?

C – Yes, I am but I thought that I had just renewed my contract.

S – Actually you do qualify for an upgrade on your phone if you would like one.

C – OK so tell me more.

S – Fine. First of all, this conversation is recorded for training purposes; are you OK with that?

C – Yes.

S – Good, can I just check that I am speaking to the right person; can you confirm the name of the account?

C – Yes (name given).

S – Can confirm your name?

C – (name provided).

S – Can you confirm that you are the right decision maker?

C – Yes.

S – Can you confirm the first line of your address and your post code? Sorry, I need to need to go into these questions; we have to do for compliance reasons.

S – OK (salesperson then talks quickly about the offer and customer decides to go for one option).

S – I see that you have two phones on the account; it makes sense to do the upgrade on both phones. What do you think the other user will want?

C – I don’t know; you need to talk to him directly. He’s not based at this office.

S – Oh, that’s a shame! Can you call him now?

C – No, he is in a meeting. Can you call back later this afternoon and I will find out?

The salesperson calls later that afternoon and goes through the same routine re name, address, etc. This is interrupted by the customer, who is now more irritated.

C – Do you need to do that again? You spoke to me just two hours ago; you know who I am, and I have given you all the details you are asking for. The phone conversation was even recorded.

S – Sorry, I know it’s a pain but I have to go through these questions; it’s more than my job is worth. My manager would kill me if I did not ask these questions. We have to do this for compliance reasons.

It is probably not surprising that the outcome of the two conversations was that the customer hung up.

What is ethical selling?

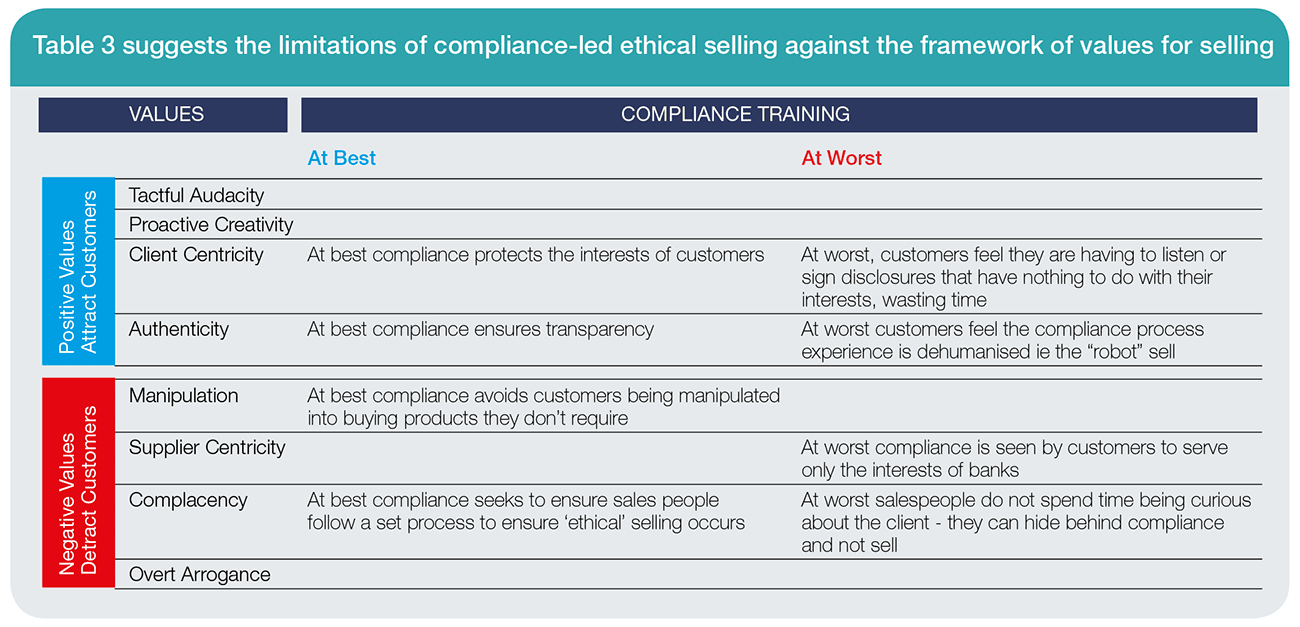

A discussion with the sales enablement team of a major international bank led to a deeper refection of the extent to which compliance training promotes ethical selling behavior. The bank’s managers are of the view that if their sales staff undertook compliance.

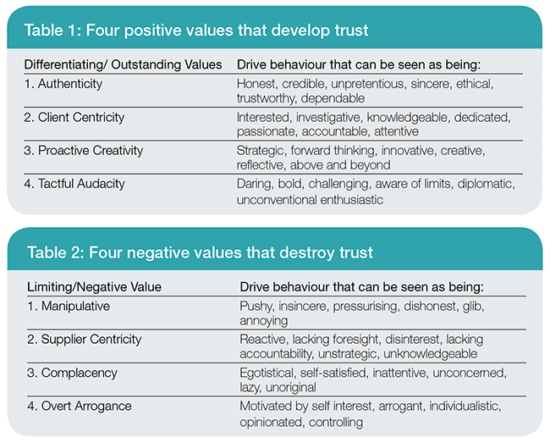

A doctoral research study of the values customers look for in selling (Squire 2009) suggests an ethical selling framework. The research describes four positive values that develop trust (table 1) with customers and four negative values that destroy trust (table 2).

A customer’s trust is gained once they feel a salesperson demonstrates authenticity and is focused on their requirements – client centricity. Trust deepens once the salesperson in addition displays the values of proactive creativity and tactful audacity. The customer wants a salesperson to suggest ideas they have not thought of and to be bold in challenging a customer if they feel the customer is making the wrong decision or if they are particularly convinced a new “idea” will benefit the customer.

With one caveat, that the customer recognizes that the “idea” is grounded in a sincere and genuine belief that it will benefit the customer. According to Squire’s research, less than 10% of salespeople demonstrate all four positive values when selling.

The negative values described above, relate to those behaviours customers observe in salespeople they don’t like. It is easy to see a connection between the negative values described and the summary sales conversation earlier (that many of us will have witnessed from mobile phone operators trying to sell new contracts).

Ironically, many of the “mis-selling” issues that compliance training seeks to protect consumers from achieve just the opposite. There is so much the salesperson has to communicate in a short space of the time (much of this compliance related) that the conversation is rushed, including the explanation on the “offer” resulting in customers feeling they are being coerced into making a decision. To add to the irritation, the customer feels manipulated – overall a very poor sales experience.

Code of practice

Clearly there is a requirement for setting of an ethical code of practice in sales but the limitations of this being governed by the HR or Legal department have been argued earlier in this paper. Other professional groups such as accountants, doctors, lawyers and procurement professionals sign up to a code of conduct. No such code exists in sales: this is a reflection, perhaps, that sales has had no long-term established professional association.

The newly formed Association of Professional Sales has recently announced a world first: a sales code of conduct “the code”; this is publicly available and backed by a professional body serving the whole sales community, with ethics at its core. Sales professionals signing up to the code are publicly stating their willingness to be measured by their customers by the terms within it and to have their professional status within the APS at risk if they transgress the code. Salespeople will complete online education and a test, to ensure that they have considered some of the consequences of both ethical and non-ethical behaviour.

The APS acknowledges that signing up to such a code can never “prove” that a salesperson will be ethical. However, signatories to the code are proactively choosing to differentiate themselves from the rest of their peers and to their customers that they will make every effort to “do the right thing and get the right results”. Over time, we will be able to assess if this initiative has borne fruit.

Conclusion

The current approach to creating ethical standards and then enforcing them through centralized compliance programs has three significant implications for the sales force. First, sales-specific ethical standards, for the most part, don’t exist. As a result, very few companies engage in sales-specific ethical training. Given the unique ethical challenges of the sales environment and the “cost” to the company of unethical decision making and behavior by the sales force, it is surprising then to see that most companies consider the centralized organizational ethics-compliance program as sufficient for sales ethical training.

A second implication is that, while most sales managers do not manage or control the company’s ethics and compliance programs, they are held responsible for the ethical conduct of their salespeople. Not surprisingly, the highest incidents of corporate unethical behavior are in organizations with a weak ethical culture; in these circumstances, when coupled with the external, less connected role of the salesperson, the opportunity for ethical misconduct is magnified.

The third implication is that, by disconnecting sales training from ethics training, the salesperson fails to see the connection between sales effectiveness and ethical decision making. Topics like bribery, expense account fraud, and appropriate customer communications may be covered in various ways by the sales manager, legal department or HR but their integration with the company’s ethical values often does not happen, leaving the salesperson to know the “letter of the law” but not the reason why the law exists.

References

Biskup, Robert: “The Benefits of Integrating Governance, Risk and Compliance”, The Wall Street Journal, 6 March 2014. Deloitte and Compliance Week: “In Focus: Compliance Trends Survey 2013”, August 2013.Ferrell, OC, John Fraedrich, and Linda Ferrell: Business Ethics: Ethical Decision Making and Cases, (10th ed.), NY: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2015. Squire, Philip: “How can a ‘Client-Centric Values’ approach to selling lead to the co-creation of new global selling mindset”, Doctorate of Professional Practice, Middlesex University, 2009.