Are incentives the sales industry’s narcotic?

19th December 2018 | Mark Bryce

This 2016 research conducted in the context of a programme of study leading to the MSc Professional Practice in Sales Leadership qualification seeks to understand the effects of sales force incentives and how to balance pay plans with company objectives (B2B).

Background

As a sales director of a successful office equipment business for over 20 years, I could be forgiven for being one of many in our industry who have used incentive schemes as a tool or motivator to directly impact on sales results, without actually standing back and examining their real effects in any depth and how they play a role in delivering the desired results. I may have noticed from time to time that certain incentives have had undesired consequences and corrected them, but did I really understand what forces were at play and how incentives align with business strategy, values and sales behaviours? Are we as sales leaders “addicted” to sales incentives and are they the “narcotic” of the whole sales industry? Are we in danger of falling foul to them and is there a better way to deliver sales pay plans?

Segalla et al (2006; 419) point out that B2B salespeople are often the direct link between a firm and its customers, they usually know the client better than any other employee and often work in the field away from direct supervision. Increasingly, good team work is a determining factor in winning sales and building long-term relationships. This also creates important compensation design issues for managers in charge of their motivation and how to deliver the reward. One fundamental concern for sales leaders looking at how to motivate their whole team, is understanding how to distribute their financial compensation (Ramaswami & Singh, 2003).

During my Masters course I gained new insight into intrinsic motivation, through coaching and my reading, and understanding how this can complement extrinsic motivation. From my own experience there are more forces at play when considering sales motivation other than incentives alone, emotions of the salesperson being one of them along with their values. Sales compensation indeed plays a part in sales motivation but, in order to understand incentives deeper and their effects, we must also consider all of a salesperson’s triggers when it comes to motivation, behaviour and performance.

Mallin and Pullins (2009) posit that motivating and directing the salesperson to increase productive customer relationships, whilst rewarding performance is a hot topic and one of the most pressing issues that sales leaders face today. They go on to say that separately, motivation, customer relationship building, compensation and sales controls have a vast academic literature and theory established, so we should be able to understand how all of these topics triangulate, shouldn’t we? There are also lots of different types of incentives, so how do we know which ones are the most effective and how should this all be balanced to create the “perfect storm” for a sales pay plan, can we create a “utopian” model?

A “spiffy” world

In the sales world we have come to accept there is often support from our suppliers in the form of incentives too. Generally they have become accepted as it means less emphasis on the employer to make up all of the sales rewards and compensation. These incentives are known as “spiffs” (Sales Promotional Incentive Funds) or “push money” (PM). These types of incentives have been used for decades and manufacturers use them to motivate salespeople to promote certain models they want to shift out of their stockpiles quicker or to incentivise the salesperson to promote their goods ahead of their competitors’ products.

These types of incentives can come in the form of money or merchandise paid directly to the salesperson from the supplier or sometimes they can accrue points to draw down prizes or cash rewards (Radin and Predmore, 2002). They also point out that there is concern that these type of incentives can cause negative consequences to all the stakeholders including the manufacturers, retailers, sales staff and especially customers. They are often seen as “bribes” which encourage the salesperson to recommend one product over another which may ultimately be less suited to the customer. This clearly introduces bias and borders on being unethical. As an insider researcher, I aimed to investigate all types of sales incentives and examine their effects on motivation, behaviours and performance.

What else is at play here?

Miao (2007; 417), drawing on Amabile et al (1994), points out that research into social psychology has demonstrated that intrinsic/extrinsic motivation is composed of cognitive and affective dimensions that have distinct antecedents and consequences. Therefore, relying on I/E motivation without incorporating other dimensions and catalysts may compromise research into the field of sales motivation, so we can’t just look at incentives alone for our answers. For instance, a company may have various sales control systems in place: behavioural controls (such as training, monitoring, evaluation and compensating for good behaviours) and outcome controls (such as rewards for proportion of sales volume or revenues). However, we must also consider how intrinsic motivators such as pride and personal values can help deliver sound customer relationship building.

Miao et al (2007), building on Ryan and Deci (2000), explain how the “Self-Determination Theory” contends that the increased cognitive capacity (eg challenge seeking) and elevated task enjoyment can accelerate the internalisation of extrinsic rewards (compensation or recognition). There are arguments that focussing on a salesperson’s activity as a control, negatively impacts upon how a salesperson feels (Jaworski and Kohli, 1991; Ryan and Deci, 1985, 2000.) Capability controls such as developing and rewarding salespeople’s selling skills, however, seems to impact intrinsic motivation (Miao et al 2007). Arguably there’s a balance that needs to be found that blends incentive packages and how they are delivered.

The final piece of my query was to look at how sales managers’ own practice can impact upon a salesperson’s motivation. In my early years in sales, I remember working under a sales manager who was too focussed on KPIs, spent little time on developing his team, very rarely patted anyone on the back but enjoyed dishing out criticism and was very authoritarian. He didn’t really trust anyone, rarely listened and only cared about one thing, how much override he was making – ultimately all he cared about was himself. Arguably, no matter what compensation plan or control system is in place, this will only work if it’s backed up by good leadership.

The project

My aim with this project was to research all areas of sales motivators, concentrating particularly on incentives and sales control systems, studying their effects on sales performance and also behaviours. The ultimate goal was to come up with a new hypothesis, a new hybrid model that could create the perfect conditions. This would be a model which could deliver the desired results and help build valued customer relationships, as well as good sales performances and help create intrinsically motivated staff.

The aim of this project was to deepen my understanding of the effects of sales incentives, how salespeople are motivated by them and what behavioural traits are caused by them. My project examined how sales processes are influenced by different types of sales incentives. This research also looked at how they can influence team cohesion, sales outcomes, company values, performance and the overall customer experience. I explored intrinsic and extrinsic motivators behind different types of sales plans and incentives programmes, and which ones elicit the best outcomes and performance.

The ultimate aim/objective of this research project was to produce a new “utopian” model that would point to the best way to formulate incentives and create ideal conditions, to produce the best sales performance results and behaviours. I aimed to compare my research with how we currently deliver incentives and also compared this to how other companies operate their schemes to explore if I could make improvements for overall company performance and sales “team” engagement. I identified key areas of consideration for my research:

- Motivation – extrinsic and intrinsic

- Structures of sales remuneration and packages

- Leadership – good and bad leadership traits and how they can influence sales behaviour

- Cognitive psychology

As I set out to gather my data, I used mixed methods. I decided that, due to my lack of experience as an insider researcher and how important this topic was to us all (to me and the business in particular), it was too risky for me to treat it as an action research project. I was concerned that my sales team would be concerned as to why I was investigating the effects of incentives internally and I was certain this would influence their answers to any questions around their incentives and pay plans. I wanted to consider the potential impacts my research would have before selecting my methodology.

I know my team well and some individuals would tell me what I wanted to hear or what they thought would elicit a positive prescribed response to them or their incentive programmes and pay plans, known as the Hawthorne effect, Holden (2001). Others would be concerned that I was thinking about changing the way they were paid. I felt that there was enough qualitative and quantitative data available on my chosen subject, such that I could avoid an insider company-based research project.

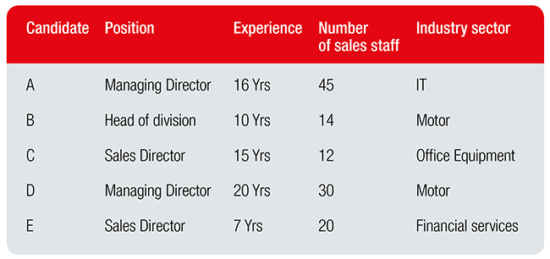

Figure 1: Interviewee profiles.

Field-based research

I met with five other sales leaders from different types of organisations (see Figure 1), paying particular attention to choosing ones who had enough experience and a relatively decent-sized sales team in order for the data to hold more credence. I held five face-to-face one-hour semi-structured interviews in which I had a prepared some open-ended questions, in order to draw out some good material around topics; these were followed up by more structured questions. The setting of each interview was at the place of work of the individual concerned and at an agreed time slot. This was pre-qualified on the day so that we were in agreement that they had enough time, without distractions, to engage.

I felt that having my own, up-to-date research would allow me to qualify/test some of my own beliefs as well as to add to the other qualitative data I was collecting. I only did this field research in my locale, so I could not rule out that this data was only significant to this region or indeed the UK. The questions were aligned to how their own sales incentives were structured: what incentives were more effective than others? What were their own thoughts on sales behaviours that were born from incentives? Did they have any team incentives in place? How did suppliers’ specific product incentives (or spiffs) play a part? What pros and cons the incentives produced and behaviours? And also discussions around the structures of pay plans and how heavily they were weighted by incentives, what worked and what did not.

The interviews and questionnaires uncovered some new material I wouldn’t have otherwise asked for by questionnaires alone and, on reflection, this was a very fruitful and fulfilling exercise. As the interviews progressed, I did modify the questions as new thought process developed and I became more experienced with this particular research path.

I have also witnessed a few instances of impacts of sales incentives and behaviours associated with them, which I recorded in my learning journal. In addition I have had opportune and often impromptu moments to discuss the topic around incentives with other salespeople from different companies and sales leaders alike. During the Masters course I have used my journal to record observations, reflections and ideas.

Quantitative analysis

Although the majority of my research was qualitative, I also utilised a select amount of data relating to pay structures, as this would form part of my theory. I examined a selected amount of information relating to what percentage of a salesperson’s remuneration is incentive variable pay versus fixed basic wage (across different industries) in order to understand if there is a pattern or if there is broad evidence that a large proportion of commission versus fixed pay leads to different types of behaviours and motivation. As I had only a limited time to carry out my field research, I also looked to “pre-coded” quantitative data to provide more evidence in order to construct my new model. Some of the questions in the interviews I held related to numbers and salary structures but clearly interviewing five leaders only provided me with very limited information, so I needed to expand upon this.

The topic of incentives seemed to draw intrinsic human resourcefulness out of these sales leaders. This allowed me to sit back and listen to open dialogue with a subject that was close to their hearts, as well as my own. The main downfall I discovered with semi-structured interviews, was that the candidates could tangent onto related subjects, so convergence of the data from each interview was more complicated. However, this allowed me to explore ambiguity and in-depth clarification, (Costley et al, 2010), that arguably you couldn’t yield from a structured questionnaire.

Project findings

During the interviews a pattern emerged: we all agreed that sales incentives were essential; however, the structure, implementation and delivery of them were vitally important. They all had previous instances, as had I, where some incentives had delivered undesired results, consequences or bad behaviours.

Example 1. A salesman selling fleet cars was put onto an incentive package whereby, instead of being paid on profitability of each car sold, he was paid a bonus for selling each car, no matter how much profit was in each vehicle. Now usually the cars in this sector would shift in bulk numbers with low margins to car leasing firms looking to offload large quantities at a time. The margins in this sector were usually small and even low adjustments in this margin could make the difference between selling a handful of cars or hundreds of them.

Once the salesman realised he could drop margin and shift lots more cars, (reducing the company’s profits in the process) he began to “dump” hundreds of cheaper cars onto the market (the lease firms were lapping this up). He earned nearly three times as much as he previously made and didn’t seem to care that there was no margin left in the cars he was selling: a clear example of selfish behaviour catalysed by the incentive. The company later moved these low-margin sales to a telesales team that were used to relatively lower rewards for making sales but were more intrinsically motivated as a team to achieve the companies objectives, again confirming that misuse of extrinsic rewards can promote bad behaviours, especially if there’s no balance or other sales controls involved to prevent it.

Example 2. In one of the interviewee’s car dealerships there was a “spiff” scheme from the manufacturer to promote the sale of a certain model of 4 x 4 vehicle. This incentive was so lucrative that some of the sales team tried to promote the car to just about every potential customer who walked through the door, even if they didn’t really need or want this particular car. There was a high risk that the customers would be persuaded to buy cars that they didn’t really need and the clients’ overall satisfaction with their experience would be overlooked. This particular dealer principal, had like most of us, fallen into the trap of allowing the supplier to dictate what the sales guys were selling, albeit producing sales but perhaps not with company or client objectives/values in mind.

We were all in agreement that spiffs should complement a sales salary package and not be so appetising as to act as a control and allow the suppliers to dictate company sales, which could be against the firm’s own sales objectives. In short, they should align with the company’s overall objectives and controlled, if indeed used at all.

Three of the people I interviewed confirmed that they had introduced “team incentives” quite successfully and that incentives spread across a whole team instilled good team spirit and behaviours.

The following common themes were drawn from the five interviews:

- Incentives were necessary but needed to be controlled.

- Incentives (outside of commissionable pay) that were in place for a long periods became a concession or expected, rather than an incentive. They were taken for granted or lost their desired effect. Withdrawing long-term incentives can also be seen as a pay cut and arguably a cause of negative effects including employment law issues such as “constructive dismissal”.

- “Spiffs” can be dangerous if they are not controlled or align to company objectives, their effects need to be considered before implementing them. On the positive side, this is a way of a supplier making up some of a salesperson’s remuneration and lowers the financial burden for incentives from the company.

- If a sale is elongated, complex or of high value and the salesperson’s contribution to it substantial, then the reward should reflect this. Subsequently, If there is relatively low involvement or influence, the sale is less complex and of lower value, then the commission should be proportionately lower.

- They all agreed that sales training and development was essential for good behaviours, intrinsic motivation and staff retention.

- Sales leadership and motivation of the sales team plays a huge role in their success or failure.

- Percentage of sales remuneration of fixed pay versus variable – This seems to vary throughout different industries and even within the same companies. From the limited information that I had here, it was inconclusive. Some salespeople are better than others and are on the same basic/fixed pay to colleagues around them but earn, relative to their sales, much more commission than the lower-performing sales staff. As long as the commissions linked with profits/revenues, then there was no need for there to be a ceiling on the amount a salesperson can earn. This also resonates with my own belief that ,if a salesperson is earning a larger amount of commission, so should the company in terms of profits. Where a salesperson’s salary becomes an impact on profits, is usually when the fixed basic salary is altered.

- Team incentives can bring about more team cohesion, act as good team motivators and complement individual incentives.

Encounters recorded in the learning journal

An interesting day out at Google London UK headquarters brought about an impromptu discussion with a senior figure within their business, who gave me some valuable insights into how they treat incentives. An interesting incentive that they had introduced, and arguably one that does bring about intrinsic motivation, is that they allow each employee to give out a £100 reward to a member of staff who they think has really made a great effort or has done something out of the ordinary, to help them, the company or indeed a customer. They allow donations of up to £500 per employee in each financial year, so the rewards are more limited and “special”. This lifts team spirit and is an interesting concept – for a company of this size it must have required some thought.

Another encounter I had was with a car salesperson (working in a dealership of a well- known brand) who openly admitted that a “spiff” incentive from the manufacturer to promote a specific model caused her to sell that particular model over any other. Arguably the customer may have purchased a car they may not have otherwise bought but again would the customer have purchased the car if they didn’t want to? Aren’t there other factors at play? Some customers are indecisive and others the opposite and know what they want, no matter how good the salesperson is at influencing their decision.

Conclusions

Throughout this paper I have expressed some of my own views alongside those I’ve researched. Drawing from all of the above research and my own experiences, a thematic analysis of the data concludes the following. In order for a sales pay/incentive system to function properly and create the desired behaviours and performance that align with company objectives, then there must be:

- A good balance of intrinsic and extrinsic motivators at play.

- A well-thought-out sales control system (SCS) involving both activity control and capability control.

- A sales training and development programme should be in place, enhancing things such as product knowledge, client centricity, sales mindsets, sales techniques and time management, and discussing career paths.

- Good leadership should be in place, knowing and understanding motivation and how to implement intrinsic motivation, deliver the correct balance of sales controls and reward structures. Coaching should play a part in sales team guidance whether it be from the leader or an outside source.

- Measures should be in place to control “spiffs” from suppliers – as long as they align with the company’s objectives and don’t compromise sales, they are usually fine.

- Make sure short-term incentives are communicated as short-term incentives – there is a danger that some incentives, if withdrawn, can be construed as pay cuts if they have been in place too long.

- Put in place a team incentive that compliments ongoing individual schemes, not replacing one with the other, to bring about more team ethic, effort and camaraderie.

- Don’t over-deliver incentives and fall foul that they are the only catalyst to produce great productivity from your sales teams. Don’t be addicted to incentives and use them wisely taking time to think about their effects before implementing. Make sure incentives are aligned with the salesperson’s interests as well as those of the firm.

- Commissions paid, should (in general) be proportionate to a salesperson’s time, effort and involvement, as well as the influence they make towards their sale. Some salespeople are involved all the way through from the prospecting to the final sale and then beyond with account management, so it should be commensurate. Ergo, the reward should also be proportionate to the value of the sale to the business.

Things to consider:

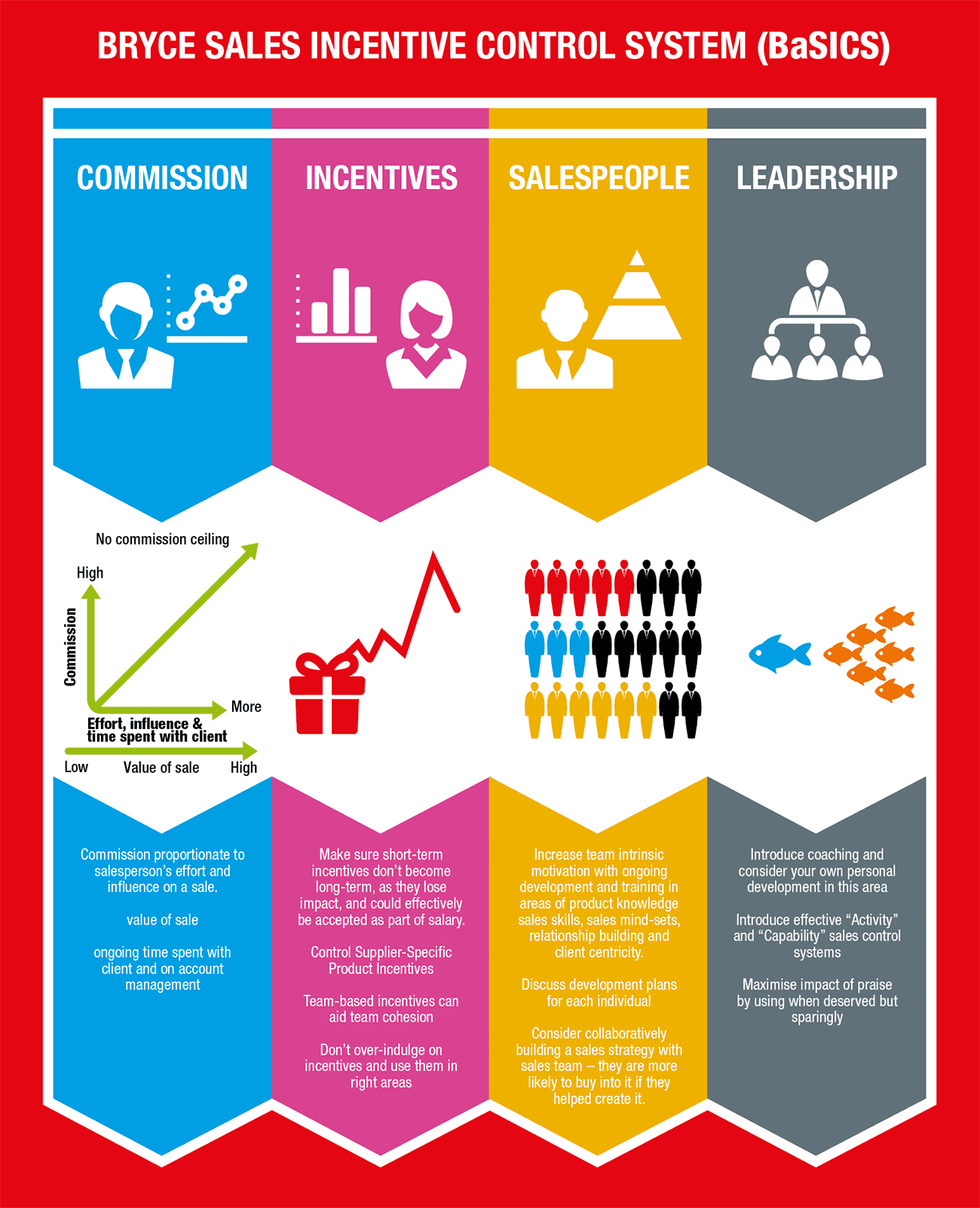

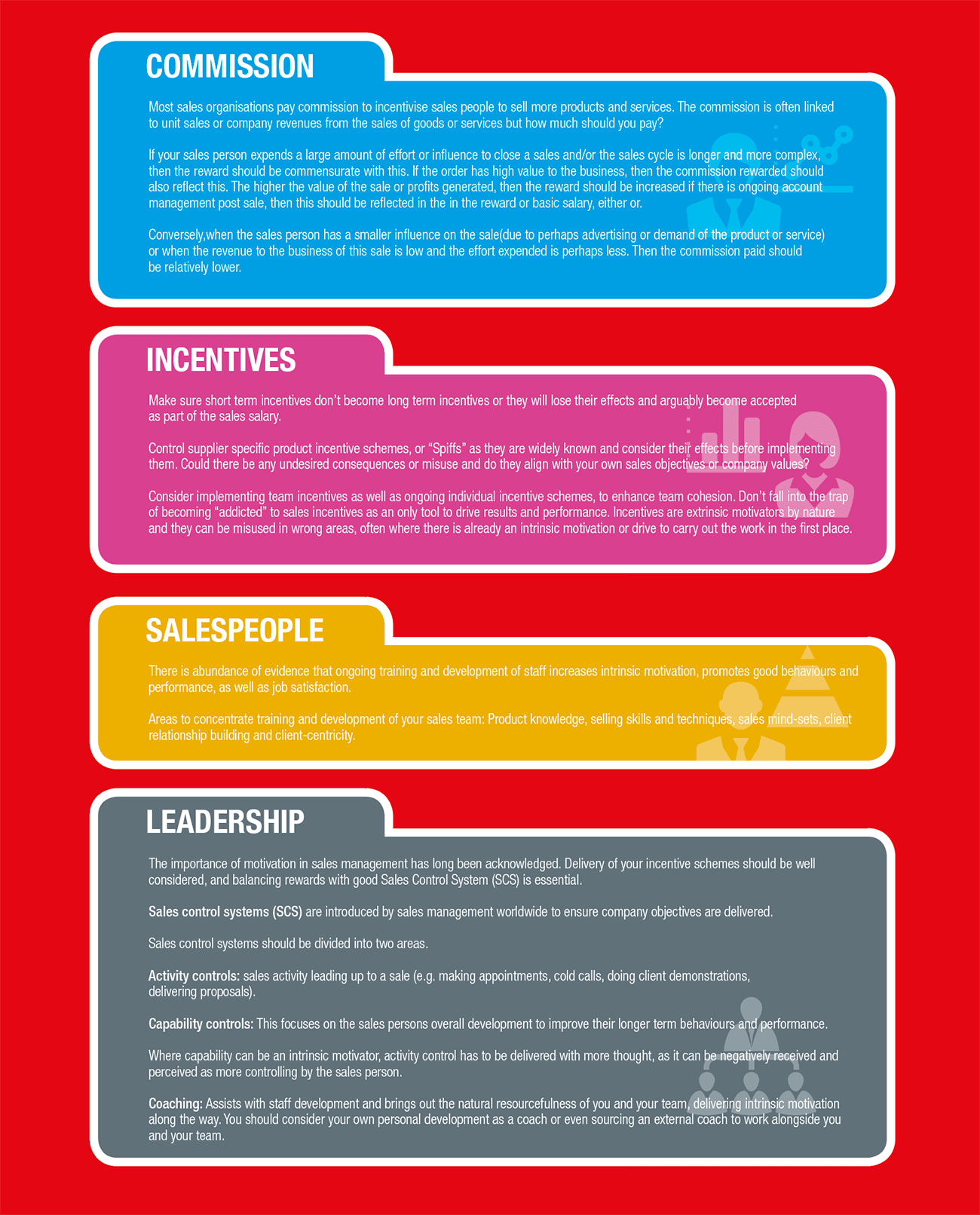

New model

The new model is called the Bryce Sales Incentive Control System (BaSICS) – see below. Its design takes into account all the motivating factors involved in a successful sales system and is an indicator of how all B2B sales reward and sales control systems should be structured to produce the best performance, motivation and behaviours.